1962 Seattle World Fair

Traditional Kustom Hot Rod and Vintage Culture and design :: Architecture: mid century modern, Googie, Art deco :: World's Fair - Expositions universelles

Page 1 sur 2

Page 1 sur 2 • 1, 2

1962 Seattle World Fair

1962 Seattle World Fair

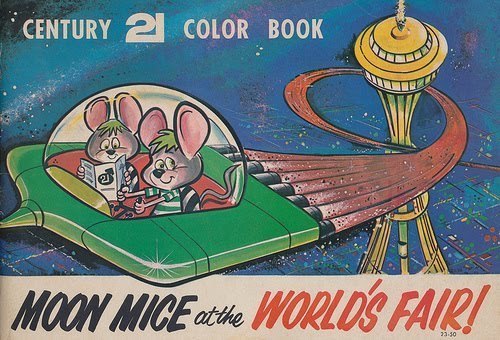

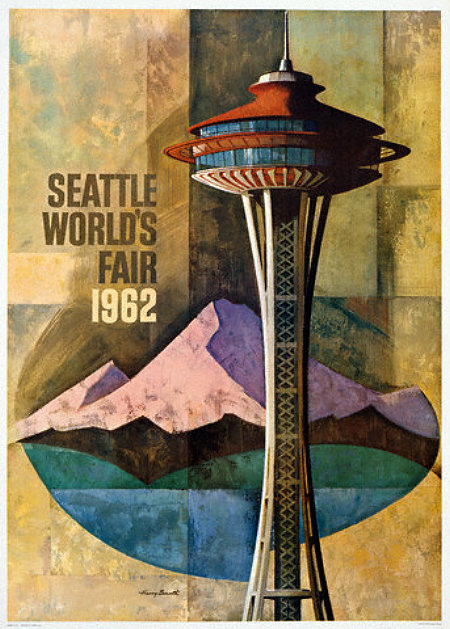

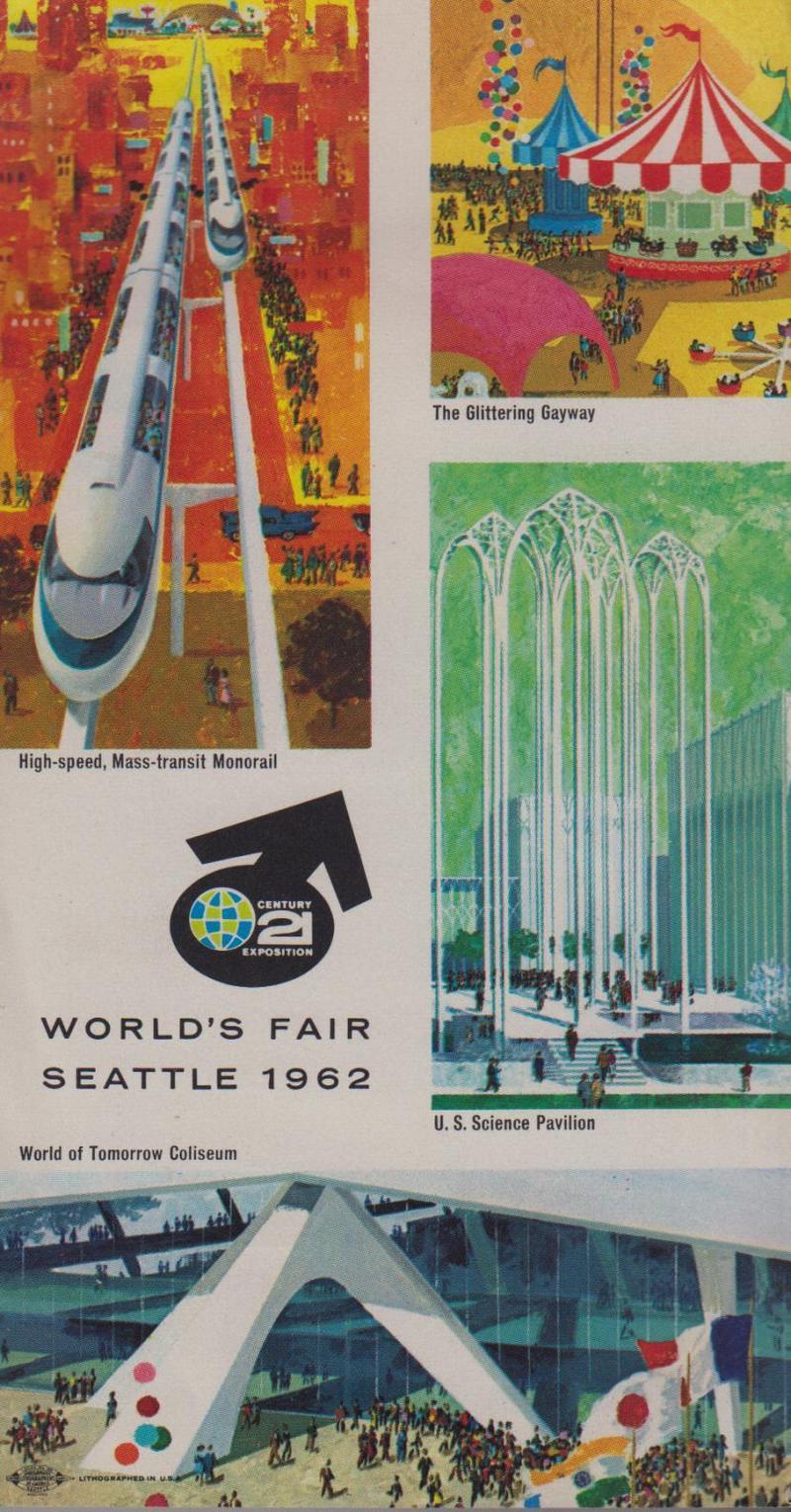

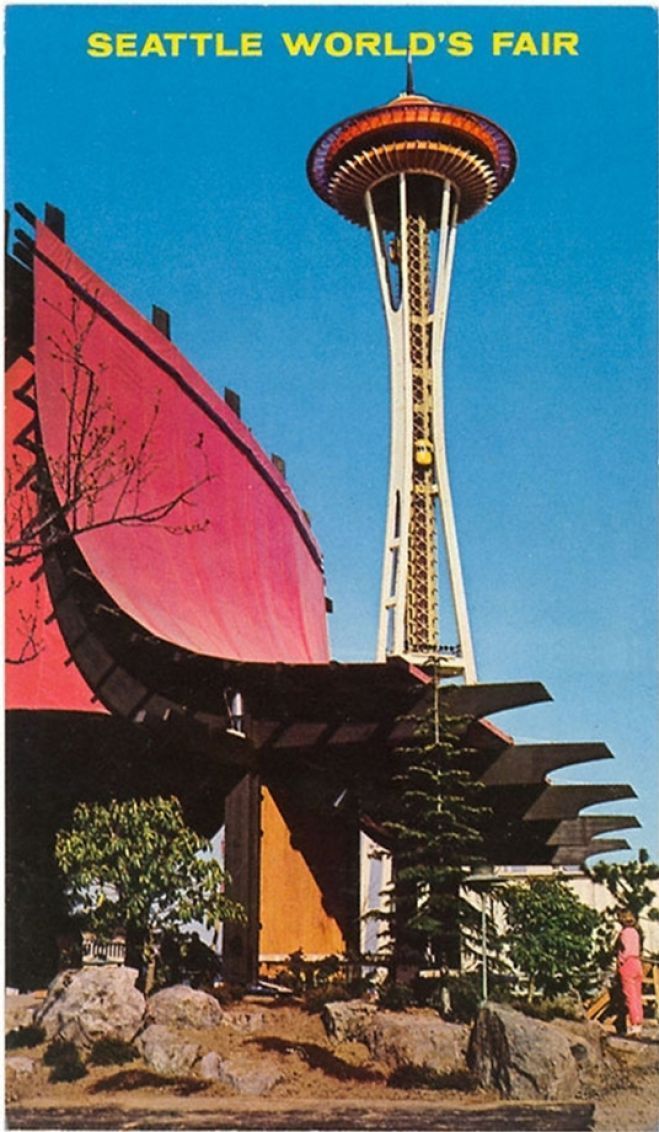

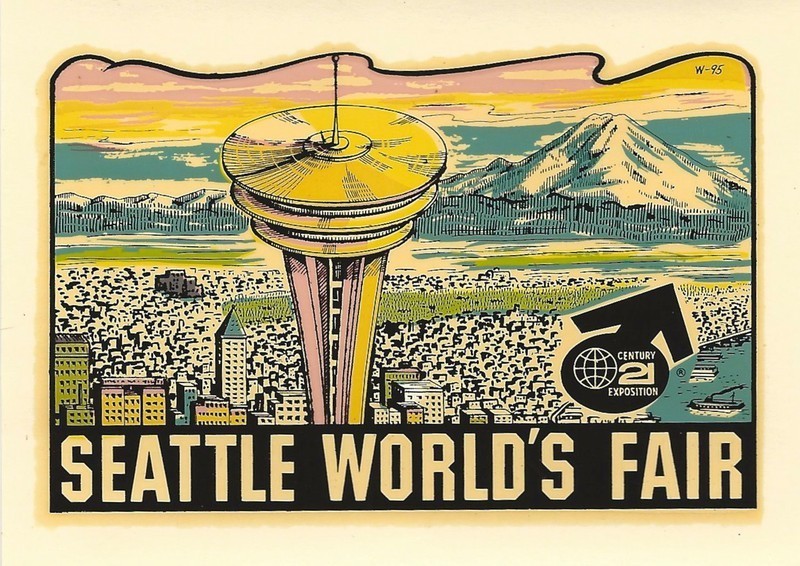

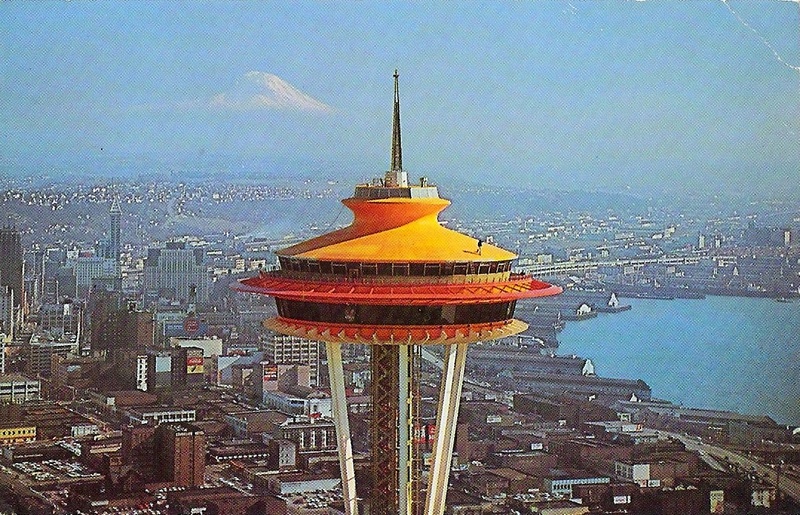

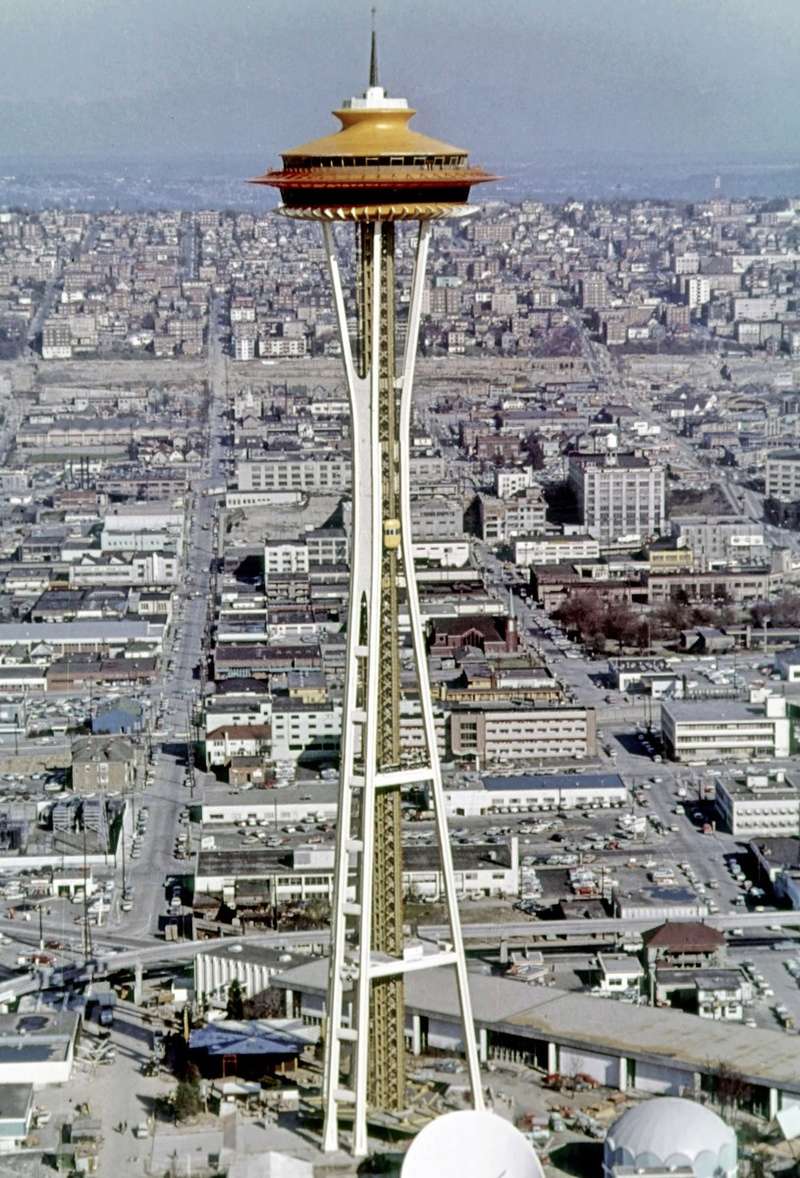

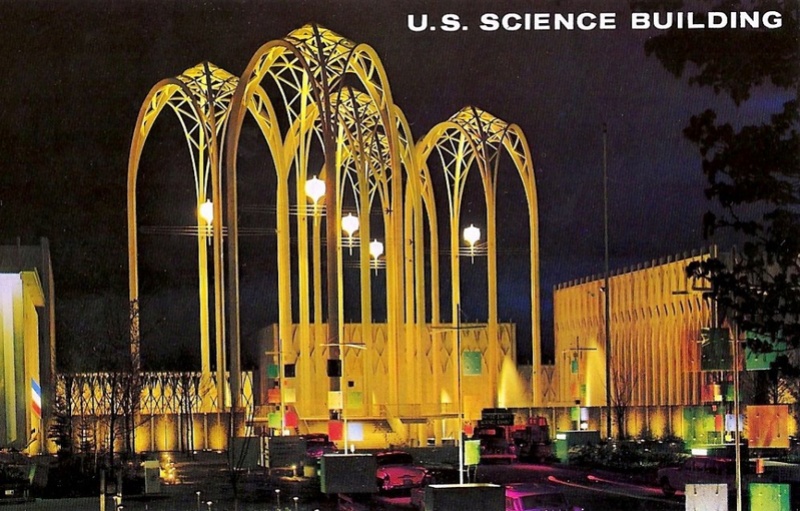

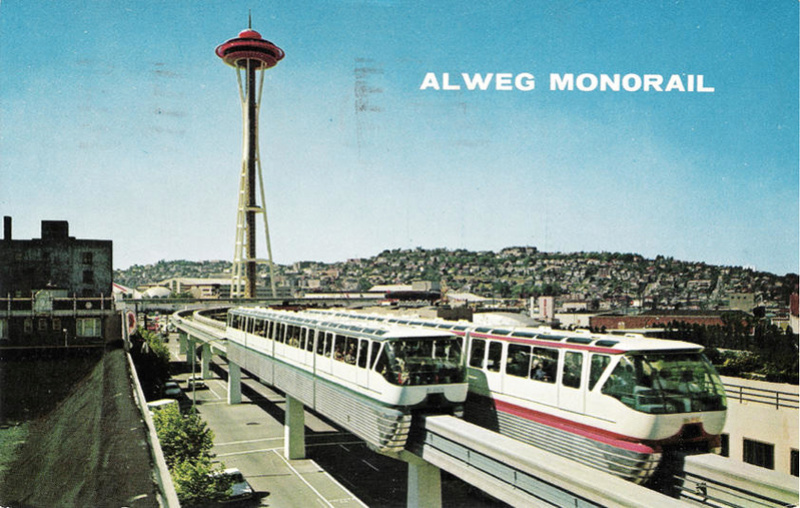

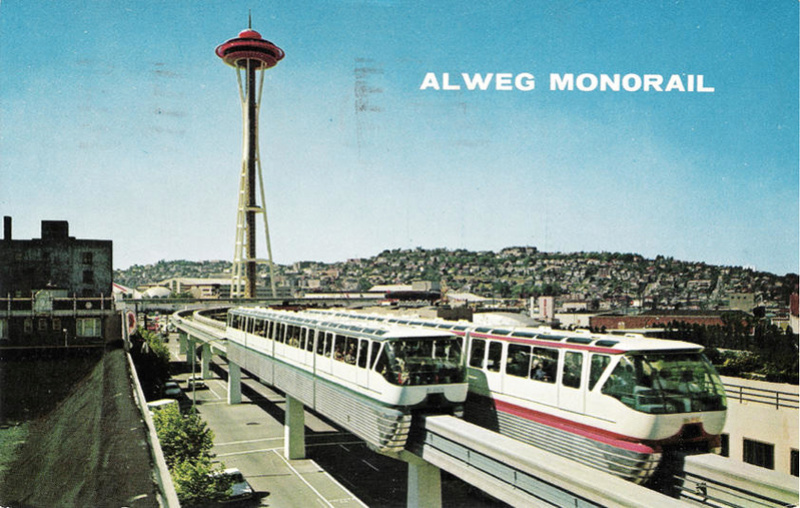

The Century 21 Exposition is best remembered for the creation of Seattle's Space Needle and Alweg Monorail. Much of what was created still exists today, including the United States Science Exhibit which is now the Pacific Science Center.

It is also remembered for Elvis Presley's movie, It Happened at the World's Fair.

This exposition was Seattle's second international exposition, preceded by the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition. The Pacific Northwest also hosted expositions in 1905 in Portland, 1974 in Spokane, and 1986 in Vancouver.

https://kathykavan.posthaven.com/tag/worldsfair

It is also remembered for Elvis Presley's movie, It Happened at the World's Fair.

This exposition was Seattle's second international exposition, preceded by the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition. The Pacific Northwest also hosted expositions in 1905 in Portland, 1974 in Spokane, and 1986 in Vancouver.

https://kathykavan.posthaven.com/tag/worldsfair

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Re: 1962 Seattle World Fair

Re: 1962 Seattle World Fair

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Re: 1962 Seattle World Fair

Re: 1962 Seattle World Fair

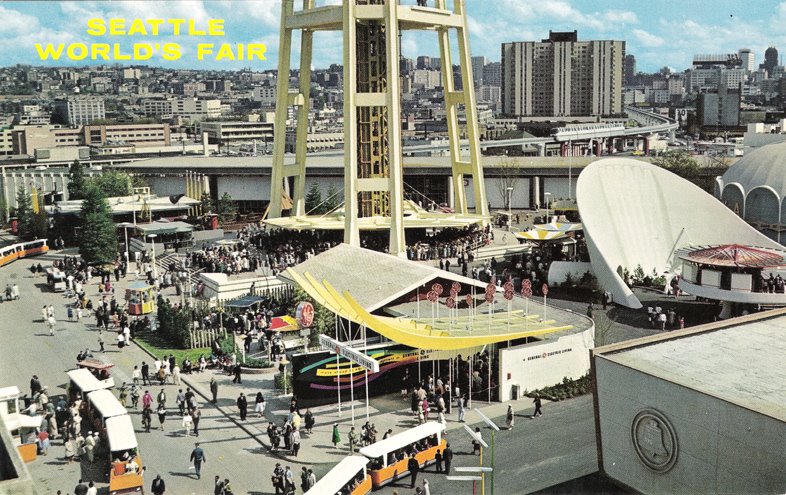

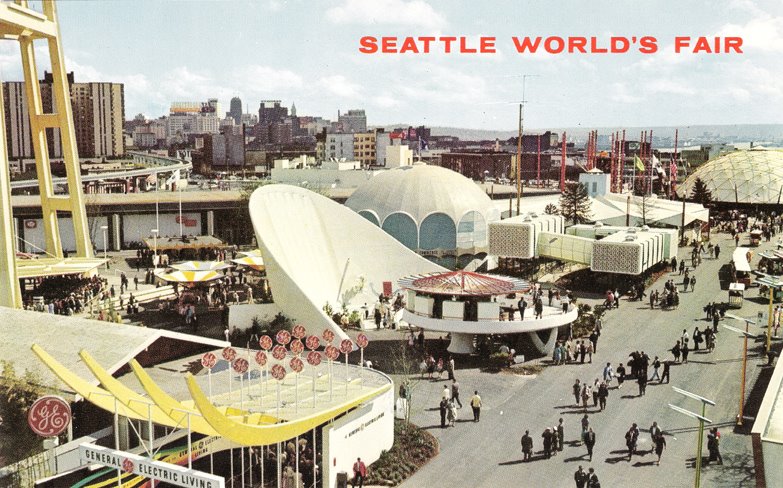

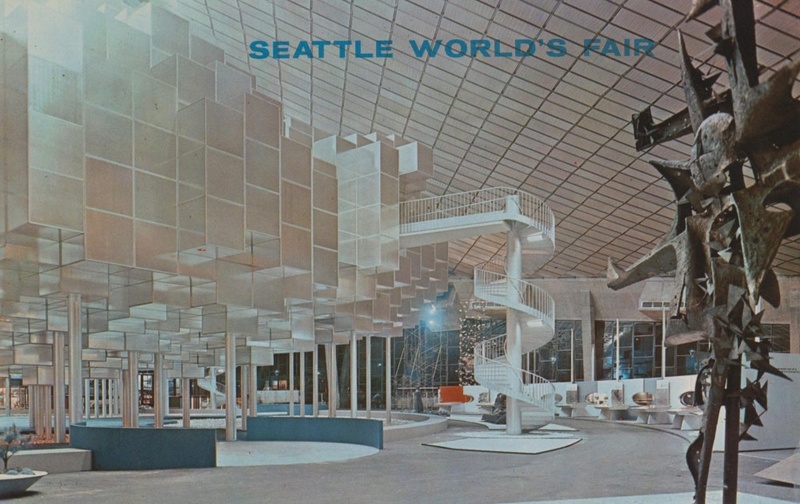

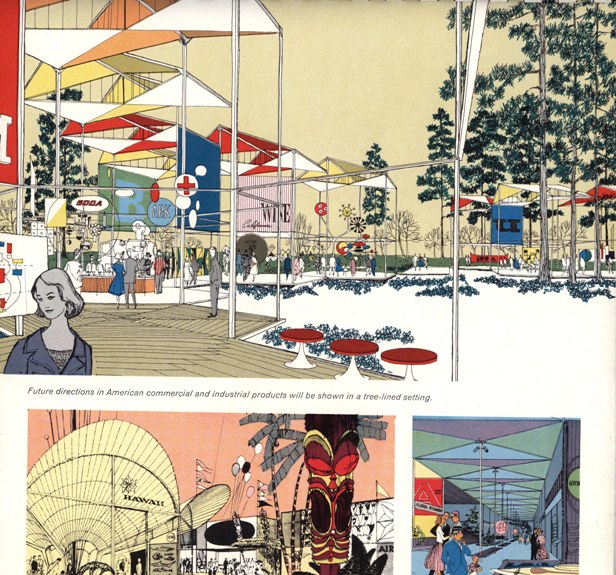

Let’s climb aboard the Alweg Monorail in Downtown Seattle and take a trip back to the 1962 World’s Fair: Man in the Space Age. The Century 21 Exposition brought the first World’s Fair in North America since 1940 and the United States was eager to demonstrate its new ideas and advancements in technology, science and entertainment. Rapid technological advancements, Googie architecture, and the Space Race tantalized imaginations with the possibilities of the 21st century and beyond. The Future promised push button telephones and flying cars. While innovations raced towards the future, values remained firmly rooted in the past. Kitchen gadgets targeted housewives while innovations in office communication targeted businessmen. Nuclear families would populate the suburbs of the Moon in the 21st century.

The Space Age theme indicated big ideas but, when compared to other World’s Fair of the era, the Exposition was a low-key event. A mere 10 million people were in attendance at Seattle’s 1962 fair—a modest turnout next to the 40-60 million who attended Brussels ’58, New York ’64, and Montreal ’67. Even President Kennedy phoned in his introduction to the fair. But there was one person in attendance whose pelvic gyrations sent many girls’ hearts flying higher than the Space Needle. Music and film sensation Elvis Presley stopped by to film some scenes for It Happened at the World’s Fair. The movie, set and filmed at the Century 21 site, is one of the rare instances of a world’s fair serving as a backdrop in a film. Other films are Centennial Summer (Philadelphia 1876), So Long at the Fair (Paris 1889), and Meet Me in St. Louis (St. Louis 1904).

Now that we’re experiencing the 21st century firsthand, we’ve seen many innovations from 1962 enter into widespread use and fall into disuse in just under 50 years. Some of the more ambitious and fantastic concepts remain dreams for a distant future. It’s nice to look back and compare the Futures of Yesterday and Today, to recall a time of innocent optimism, and perhaps tantalize imaginations with the possibilities beyond the 21st century.

Read more at: http://www.ultraswank.net/event/century-21-seattle-worlds-fair-1962/

The Space Age theme indicated big ideas but, when compared to other World’s Fair of the era, the Exposition was a low-key event. A mere 10 million people were in attendance at Seattle’s 1962 fair—a modest turnout next to the 40-60 million who attended Brussels ’58, New York ’64, and Montreal ’67. Even President Kennedy phoned in his introduction to the fair. But there was one person in attendance whose pelvic gyrations sent many girls’ hearts flying higher than the Space Needle. Music and film sensation Elvis Presley stopped by to film some scenes for It Happened at the World’s Fair. The movie, set and filmed at the Century 21 site, is one of the rare instances of a world’s fair serving as a backdrop in a film. Other films are Centennial Summer (Philadelphia 1876), So Long at the Fair (Paris 1889), and Meet Me in St. Louis (St. Louis 1904).

Now that we’re experiencing the 21st century firsthand, we’ve seen many innovations from 1962 enter into widespread use and fall into disuse in just under 50 years. Some of the more ambitious and fantastic concepts remain dreams for a distant future. It’s nice to look back and compare the Futures of Yesterday and Today, to recall a time of innocent optimism, and perhaps tantalize imaginations with the possibilities beyond the 21st century.

Read more at: http://www.ultraswank.net/event/century-21-seattle-worlds-fair-1962/

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Re: 1962 Seattle World Fair

Re: 1962 Seattle World Fair

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Re: 1962 Seattle World Fair

Re: 1962 Seattle World Fair

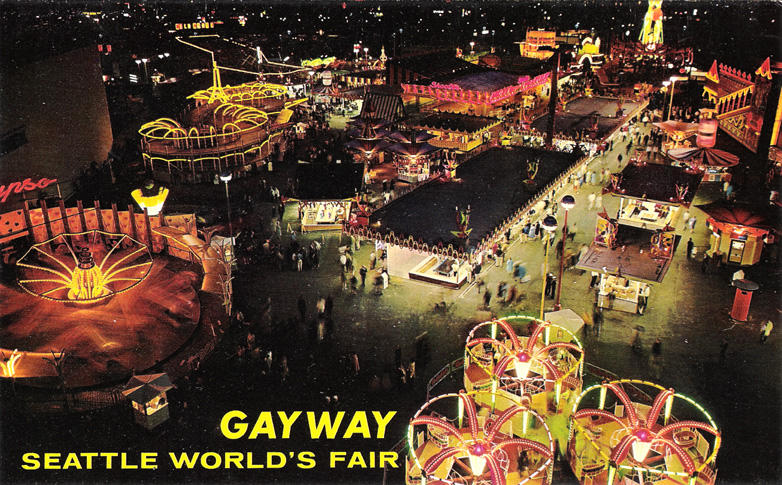

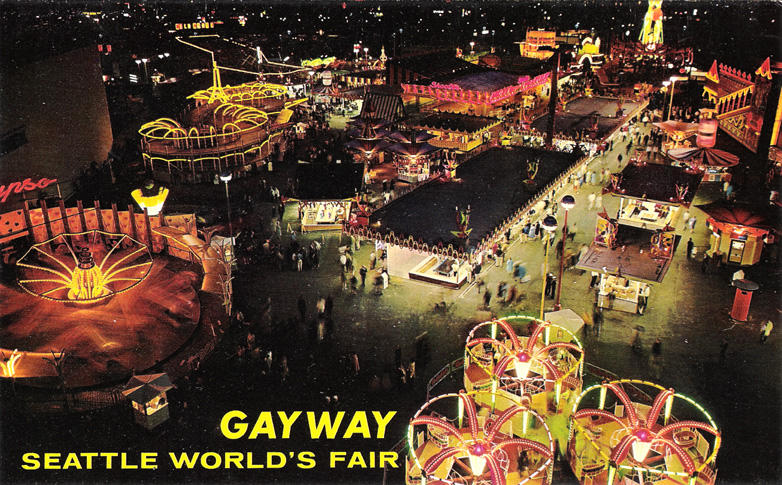

The Seattle World’s Fair in 1962 with the theme Century 21 has to be the coolest fair ever! Go from downtown Seattle on the monorail, speeding along high above the streets of Seattle. The fair was home of the Space Needle, one of the most famous Googie architecture landmarks in America, it still stands there today if you want to visit it. It was also home of the Bubbelator science ride, which took up to 150 people in a transparent sphere with the eerie space music of Attilio Mineo playing in the background. Do not forgot to take the Gayway and visit the Swedish exposition for a bite of their famous Smorgasbord.

Read more at: http://www.ultraswank.net/event/ride-the-monorail/

Read more at: http://www.ultraswank.net/event/ride-the-monorail/

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

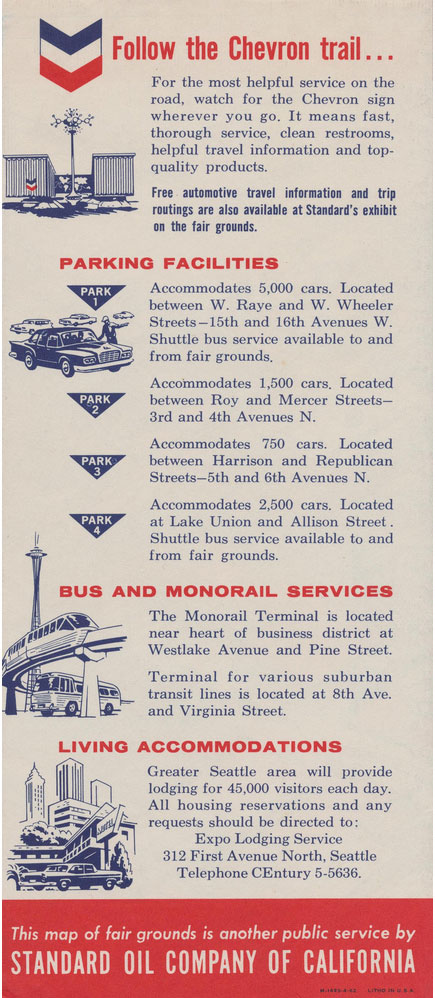

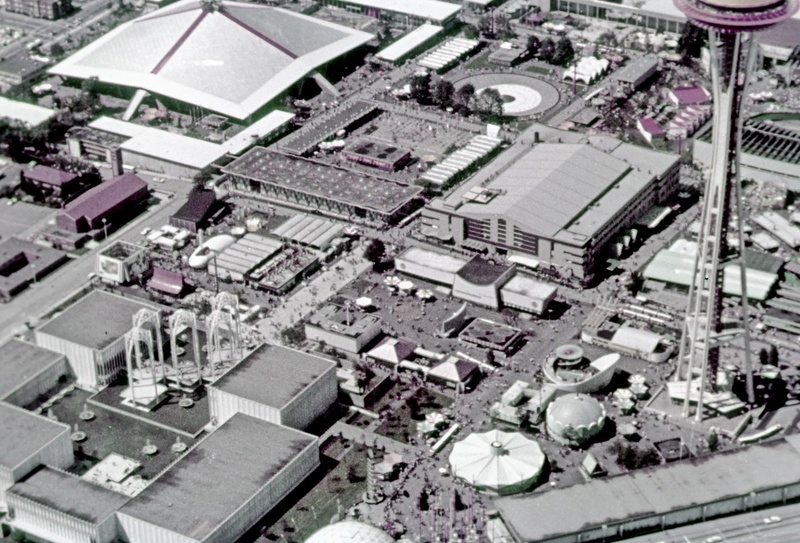

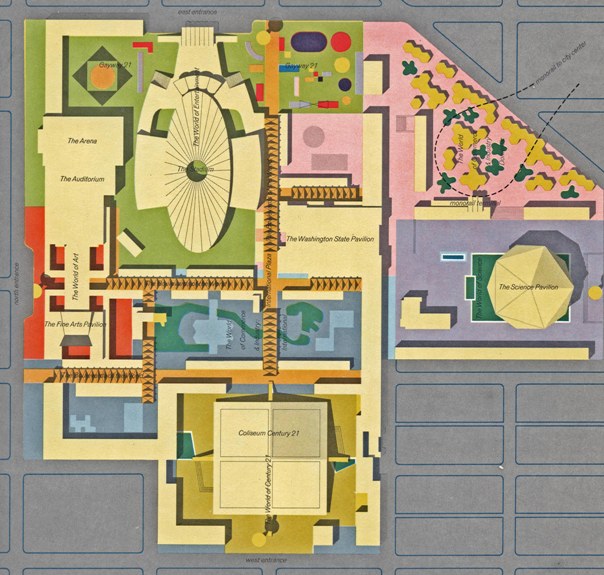

Seattle World's Fair 1962 Map of the Fairgrounds

Seattle World's Fair 1962 Map of the Fairgrounds

1. U.S. Science Pavilion

2. Bank Building

3. U.S. Plywood Exhibit

4. Sermons From Science

5. Nalley's Foods Exhibit

6. Club 21

7. Public Information Booth

8. Christian Pavilion and Children's Center

9. I.B.M. Exhibit

10. Hydro Electric Exhibit

11. National Bank of Commerce Exhibit

12. Alaskan Building

13. Natural Gas Exhibit

14. Ford Exhibit

15. Fashion Pavilion

16. Christian Science Pavilion

17. Forestry Building

18. Space Needle

19. General Electric Exhibit

20. Monorail Terminal

21. Food Circus

22. Bell Telephone Exhibit

23. United States Commerce and Industry Exhibits

24. Foreign Exhibits

25. Washington State Coliseum

26. Plaza of States

27. International Fountain

28. Jewels of the World

29. Chun-King Food Exhibit

30. 12,000 Seat Outdoor Stadium

31. Gayway

32. Sky Ride

33. Islands of Hawaii Pavilion

34. Show Street, U.S.A.

35. Arena

36. Opera House

37. Fine Arts Pavilion

38. Home of Living Light

39. Little Theatre Playhouse

40. Boulevards of the World

41. Toilet Facilities

Park 2 - Public Parking

Park 3 - Public Parking

A - South Entrance (Broad Street)

B - East Entrance (5th Avenue North)

C - North Entrance (Mercer Street)

D - West Entrance (1st Avenue North)

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Re: 1962 Seattle World Fair

Re: 1962 Seattle World Fair

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Re: 1962 Seattle World Fair

Re: 1962 Seattle World Fair

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Re: 1962 Seattle World Fair

Re: 1962 Seattle World Fair

https://www.seattle.gov/cityarchives/exhibits-and-education/digital-document-libraries/century-21-worlds-fair

The Century 21 Exposition - also known as the Seattle World's Fair - was held between April 21 and October 21, 1962 drew almost 10 million visitors. A defining moment in the history of Seattle, this fair began life as the brainchild of City Councilman Al Rochester. By 1955, the councilman had generated considerable interest in his idea from decision makers at the state and city level, and in January Washington's legislature allocated $5,000 for a small commission to study the feasibility of such a fair. Public excitement, spurred on by effective advertisement, soon gave the project further momentum; in 1957 Seattle voters passed a $7.5 million Civic Center bond for possible fairground development, an amount which was then matched by the legislature.

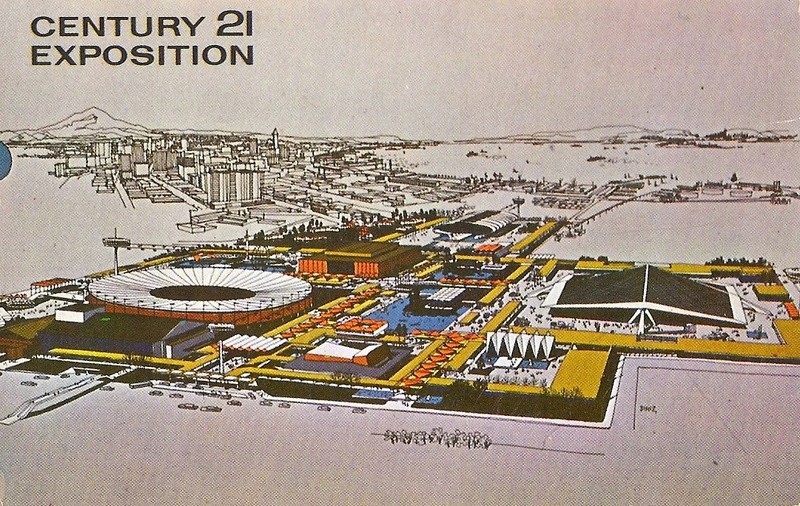

The newly-expanded Commission of 1957 decided on a theme for the Fair centered on modern science, space exploration, and the progressive future, wrapped in the broad concept of a 'Century 21 Exposition.' A 28-acre parcel of city-owned land near Queen Anne Hill was eventually chosen for the site of the Fair over larger and more nominally attractive sites such as Fort Lawton (800 acres) and Sand Point Naval Air Station (350 acres). The site's proximity to the downtown area, as well as the interest in converting the Exposition's permanent facilities into a Civic Center after the fair made this location attractive to the planners.

Early planning continued into 1960, when the Century 21 Commission, after considerable lobbying, secured from the International Bureau of Expositions a certification as an official World's Fair. International confirmation provided a powerful legitimacy among the various entities the Fair's representatives sought to attract as funders and exhibit-builders. Enticed by the publicity possibilities inherent in the millions of fair-goers projected to appear, several giants of American business decided to sponsor exhibits in the 'World of Commerce and Industry' section of the Exposition, including Ford Motor Company, Boeing, and Bell Telephone.

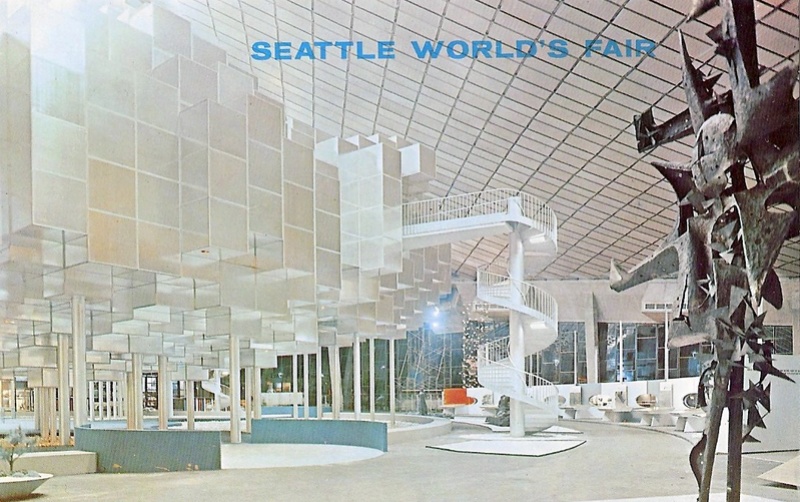

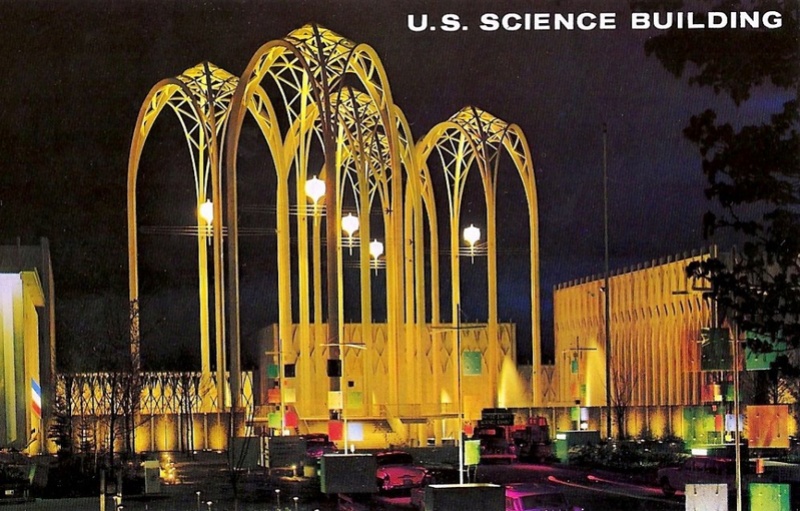

The US Government, for its part, was exceedingly interested in demonstrating the nation's scientific prowess to the world, and so committed over $9 million to the fair, chiefly to build the NASA-themed United States Science Exhibit (now the Pacific Science Center). A number of foreign governments provided the international flavor crucial to a World's Fair, and eventually 35 states signed on as exhibitors. The tense geopolitical mood of the early 1960s, however, limited involvement of the Communist states; the Soviet Union declined to participate, and the People's Republic of China, North Vietnam, and North Korea were not invited.

To coordinate the overarching blueprint of all these exhibits, respected designer Paul Thiry was hired as chief architect of the Exposition. Thiry was also tapped to design the Washington State Pavilion (now the KeyArena), the conceptual centerpiece of the 'World of Tomorrow' section. Under the supervision of Thiry, the World's Fair Commission, and the city's Civic Center Advisory Committee, the ideas and plans of many differing minds began to take shape in the fairgrounds at the base of Queen Anne Hill, gradually creating an aesthetically adventurous cityscape intended to excite the visitor with futuristic visions of scientific progress.

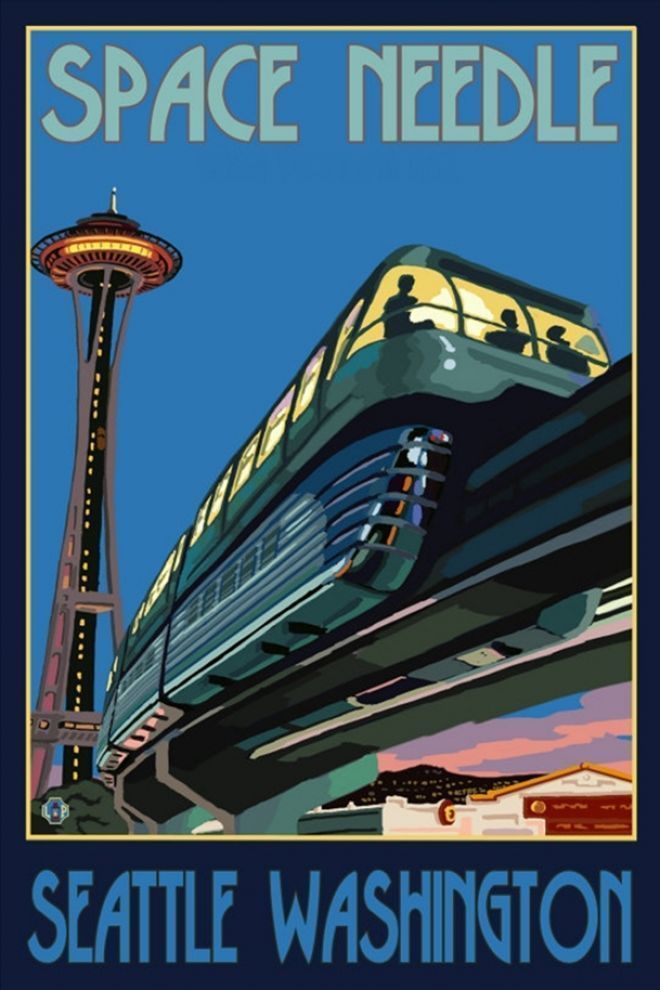

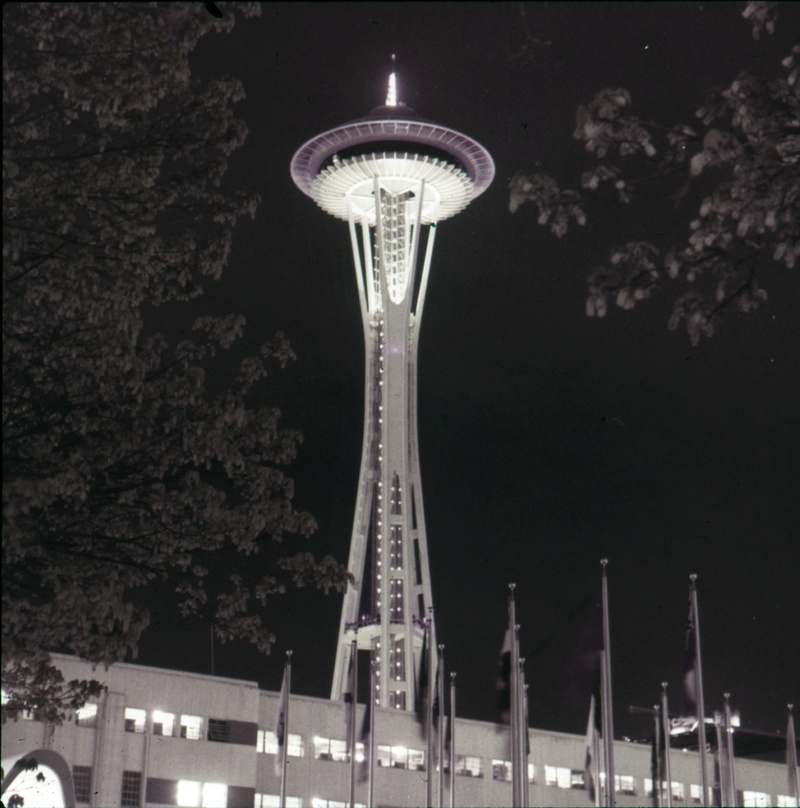

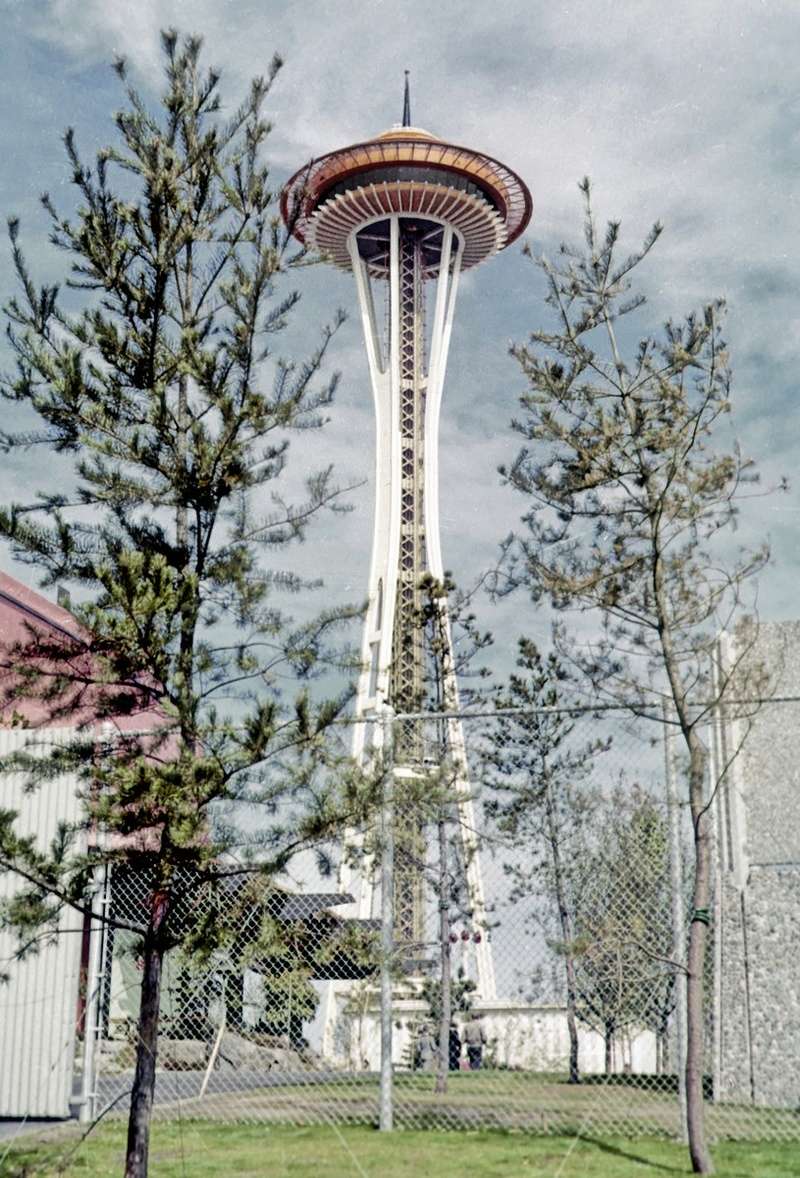

Reinforcing this sense of futurism was the ultra-modern Monorail line developed to ferry tourists from downtown Seattle to the fairgrounds. Those searching for more conventional entertainments would be catered to as well, with the construction of the 'Gayway' (a small amusement park that would become the Fun Forest) and 'Show Street' (the "adult entertainment" section, featuring a number of bars, restaurants, and nightclubs). The visual centerpiece of the fair, ultimately, would also become an icon of Seattle: the Space Needle. This 605-foot, $6.5 million rotating restaurant tower was considered a risky investment because of its grandiose dimensions and spectacular design. The needle was nonetheless wildly popular among fairgoers, and has remained a well-loved tourist attraction.

By April 1962, all that remained to be done was to open the doors to the public, which occurred during an extravagant opening ceremony on the 21st. Amidst 538 clanging bells, 2000 balloons, and 10 Air Force F-102 fighters swooping overhead, Exposition president Joseph Gandy officially opened Century 21 for business. For the next six months, visitors would be entertained not just by the many exhibits, but also by an array of musicians, orchestras, dance troupes, art collections, singers, comedians, and other various shows traveling through the fair during its run. Adding to the star-studded atmosphere was the presence of the 'King of Rock and Roll,' Elvis Presley, who arrived to shoot a film, It Happened at the World's Fair. Indeed, a number of celebrities came to the Exposition as tourists, including Vice-President Lyndon Johnson, Walt Disney, and Prince Phillip of Great Britain. By the close of the fair on October 21, a total of 9,609,969 people officially visited, largely satisfying attendance goals.

The Century 21 Exposition - also known as the Seattle World's Fair - was held between April 21 and October 21, 1962 drew almost 10 million visitors. A defining moment in the history of Seattle, this fair began life as the brainchild of City Councilman Al Rochester. By 1955, the councilman had generated considerable interest in his idea from decision makers at the state and city level, and in January Washington's legislature allocated $5,000 for a small commission to study the feasibility of such a fair. Public excitement, spurred on by effective advertisement, soon gave the project further momentum; in 1957 Seattle voters passed a $7.5 million Civic Center bond for possible fairground development, an amount which was then matched by the legislature.

The newly-expanded Commission of 1957 decided on a theme for the Fair centered on modern science, space exploration, and the progressive future, wrapped in the broad concept of a 'Century 21 Exposition.' A 28-acre parcel of city-owned land near Queen Anne Hill was eventually chosen for the site of the Fair over larger and more nominally attractive sites such as Fort Lawton (800 acres) and Sand Point Naval Air Station (350 acres). The site's proximity to the downtown area, as well as the interest in converting the Exposition's permanent facilities into a Civic Center after the fair made this location attractive to the planners.

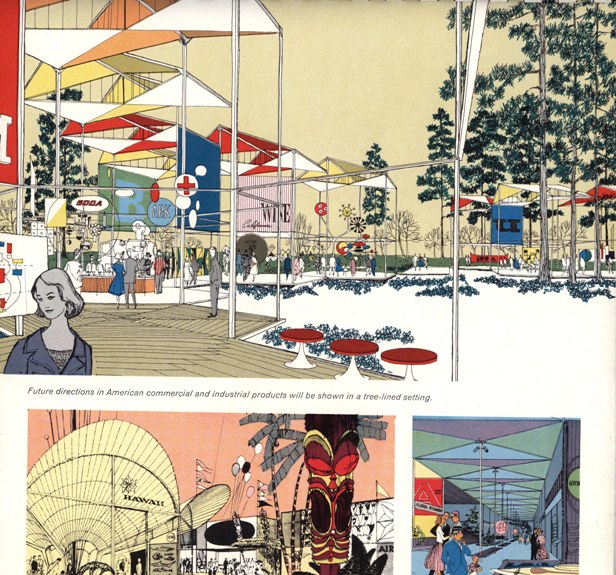

Early planning continued into 1960, when the Century 21 Commission, after considerable lobbying, secured from the International Bureau of Expositions a certification as an official World's Fair. International confirmation provided a powerful legitimacy among the various entities the Fair's representatives sought to attract as funders and exhibit-builders. Enticed by the publicity possibilities inherent in the millions of fair-goers projected to appear, several giants of American business decided to sponsor exhibits in the 'World of Commerce and Industry' section of the Exposition, including Ford Motor Company, Boeing, and Bell Telephone.

The US Government, for its part, was exceedingly interested in demonstrating the nation's scientific prowess to the world, and so committed over $9 million to the fair, chiefly to build the NASA-themed United States Science Exhibit (now the Pacific Science Center). A number of foreign governments provided the international flavor crucial to a World's Fair, and eventually 35 states signed on as exhibitors. The tense geopolitical mood of the early 1960s, however, limited involvement of the Communist states; the Soviet Union declined to participate, and the People's Republic of China, North Vietnam, and North Korea were not invited.

To coordinate the overarching blueprint of all these exhibits, respected designer Paul Thiry was hired as chief architect of the Exposition. Thiry was also tapped to design the Washington State Pavilion (now the KeyArena), the conceptual centerpiece of the 'World of Tomorrow' section. Under the supervision of Thiry, the World's Fair Commission, and the city's Civic Center Advisory Committee, the ideas and plans of many differing minds began to take shape in the fairgrounds at the base of Queen Anne Hill, gradually creating an aesthetically adventurous cityscape intended to excite the visitor with futuristic visions of scientific progress.

Reinforcing this sense of futurism was the ultra-modern Monorail line developed to ferry tourists from downtown Seattle to the fairgrounds. Those searching for more conventional entertainments would be catered to as well, with the construction of the 'Gayway' (a small amusement park that would become the Fun Forest) and 'Show Street' (the "adult entertainment" section, featuring a number of bars, restaurants, and nightclubs). The visual centerpiece of the fair, ultimately, would also become an icon of Seattle: the Space Needle. This 605-foot, $6.5 million rotating restaurant tower was considered a risky investment because of its grandiose dimensions and spectacular design. The needle was nonetheless wildly popular among fairgoers, and has remained a well-loved tourist attraction.

By April 1962, all that remained to be done was to open the doors to the public, which occurred during an extravagant opening ceremony on the 21st. Amidst 538 clanging bells, 2000 balloons, and 10 Air Force F-102 fighters swooping overhead, Exposition president Joseph Gandy officially opened Century 21 for business. For the next six months, visitors would be entertained not just by the many exhibits, but also by an array of musicians, orchestras, dance troupes, art collections, singers, comedians, and other various shows traveling through the fair during its run. Adding to the star-studded atmosphere was the presence of the 'King of Rock and Roll,' Elvis Presley, who arrived to shoot a film, It Happened at the World's Fair. Indeed, a number of celebrities came to the Exposition as tourists, including Vice-President Lyndon Johnson, Walt Disney, and Prince Phillip of Great Britain. By the close of the fair on October 21, a total of 9,609,969 people officially visited, largely satisfying attendance goals.

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Re: 1962 Seattle World Fair

Re: 1962 Seattle World Fair

City Involvement in Century 21

Though the fair was primarily administered by the non-profit private Century 21 Exposition, Incorporated, the government of Seattle was deeply involved in development and execution. Once preparations began in earnest in 1957, substantial efforts were made to integrate the planning of the municipal, state, and private entities involved. Planner Evan Dingwall, for example, simultaneously held the directorships of the Washington State World's Fair Commission and Seattle Civic Center Advisory Committee, and would later serve as general manager of Century 21 Exposition, Inc. For its part, this Advisory Committee wielded substantial influence on the design process, reflecting the long-term goal of creating a viable core of facilities for a post-Exposition Civic Center. Thanks in part to this advocacy, Seattle would inherit 400,000 square feet of permanent indoor exhibition space from the fair. In addition, the city government oversaw a number of fair-based building projects both within and beyond the fairgrounds, including the Monorail line, the International Fountain, and a 1,500-car garage along Mercer Street.

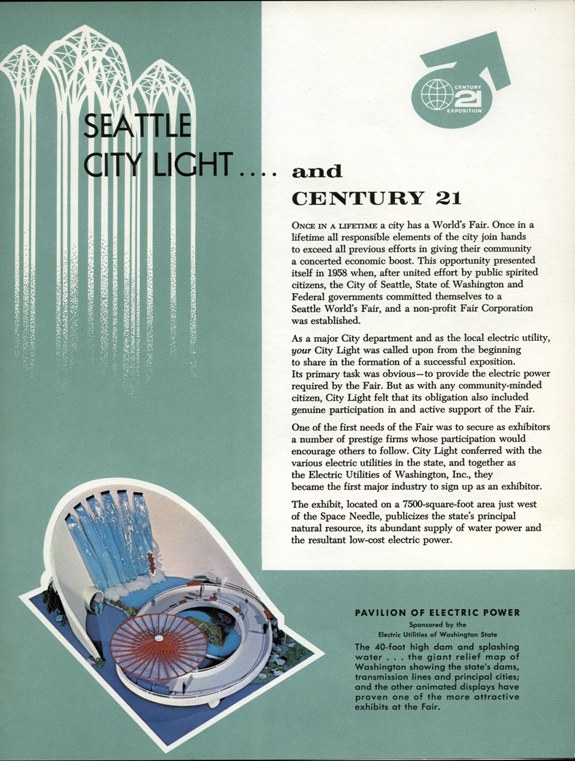

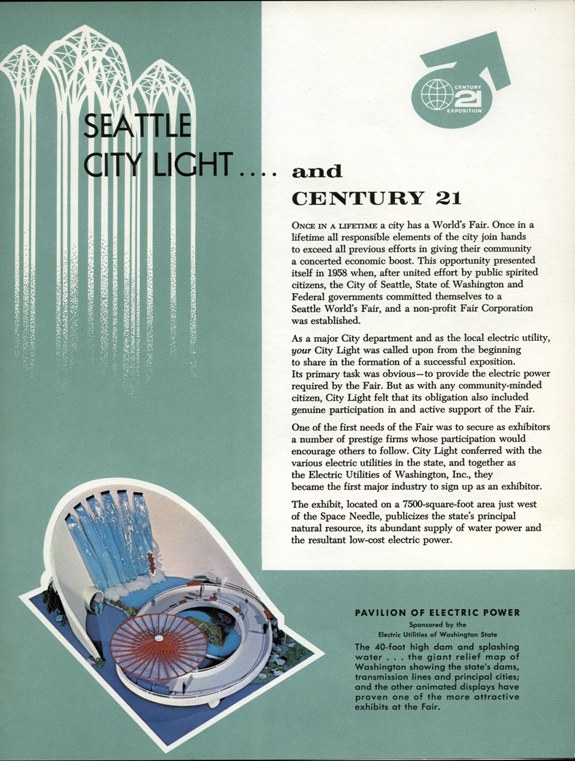

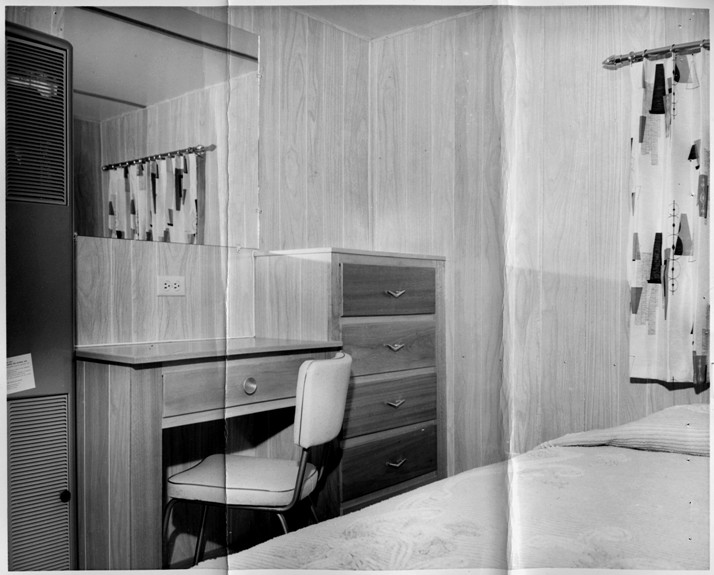

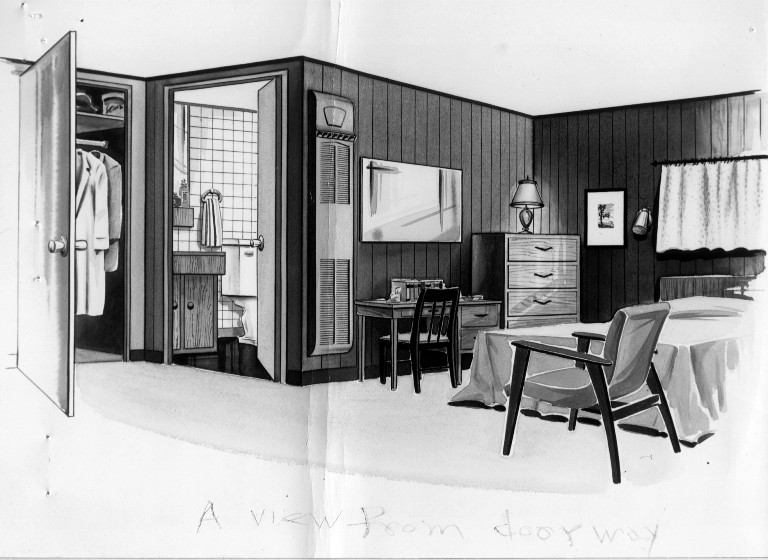

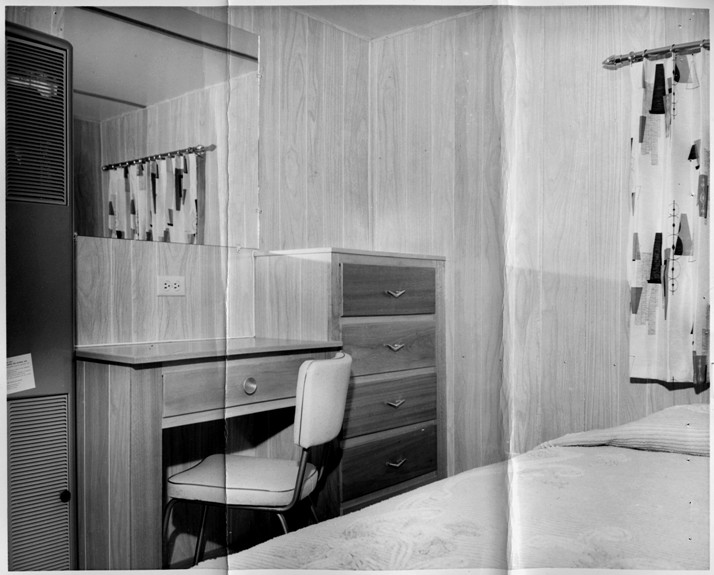

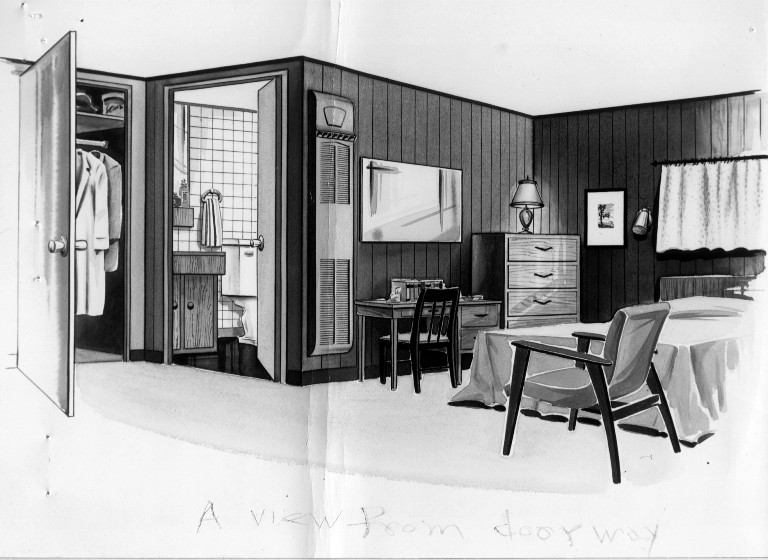

Interior photo of prototype Travel Trailer (1962)

Individual branches of municipal government also pursued a range of initiatives necessitated or provoked by Century 21. The Mayor's Office, for one, spearheaded a Downtown Beautification program that encouraged the cleanup and renovation of prominent City facilities, such as firehouses and parks. The Board of Public Works conducted oversight and licensing for building projects underway on municipal land, and so was crucial to the design and construction of fair exhibits. In 1960, $537,000 was approved to construct and install underground lighting facilities in the Century 21 site and vicinity; this involved removing approximately three and half miles of overhead pole lines. The projected influx of 10 million fairgoers prompted the Engineering Department to undertake a significant slate of improvements to the downtown transportation network, in addition to the needed incorporation of the fairgrounds into the water/ sewer utility system. Seattle City Light, finally, provided more than just the expected power to the Exposition; as a integral member of the Electric Utilities of Washington consortium, City Light played a pivotal role in developing the 'Pavilion of Electric Power,' a sizable exhibit featuring a 40-foot tall depiction of a hydroelectric dam.

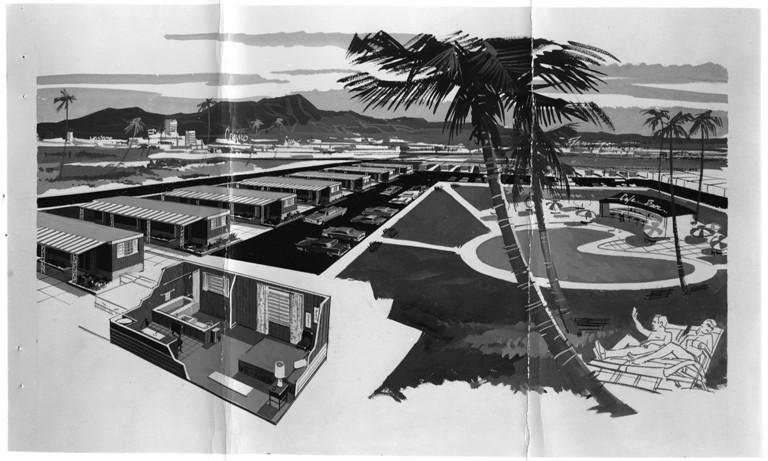

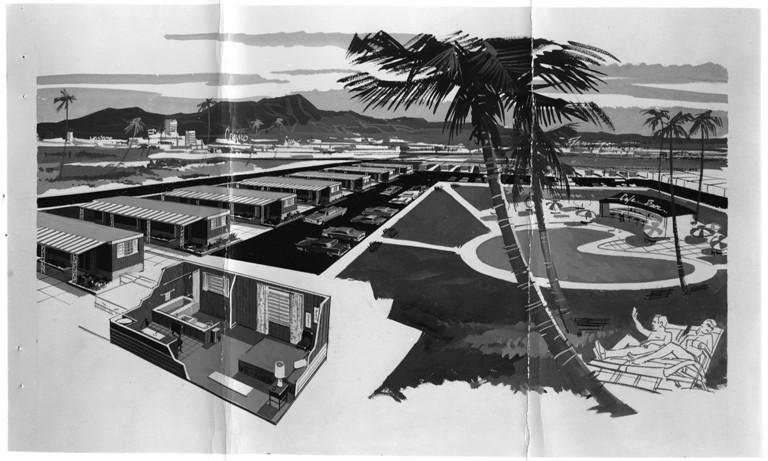

Artist's rendering of possible Travel Trailer park (1962)

Controversy: Housing at the Fair

The Century 21 Exposition has generally been considered a success by later commentators, though this does not mean it occurred without incident. A principal controversy arose from the perceived 'housing crunch' expected during the fair, as millions of tourists descend upon the city and rapidly fill up existing hotels and motels. Unless extraordinary action was taken, many felt, fair visitors would be turned away without accommodation, damaging the Exposition's reputation. As the City Council took steps to respond, such as permitting the use of docked 'marine vessels' as temporary lodgings, certain residential hotel owners sought to exploit the housing shortage. With little warning, these landlords converted their buildings, which often housed people who had resided there for years, from monthly rentals to daily. Thus, prices were raised significantly, effectively 'pricing out' long-term residents in favor of the more lucrative tourist trade. Understandably angered by their 'eviction,' many wrote emotional letters to the Mayor, City Council, and the Seattle press. Though the actual numbers of residents evicted remains unclear, public indignation ignited a heated debate over what the municipal government should do in response.

Artist's rendering of interior of prototype Travel Trailer (1962)

Public concern over landlord malfeasance climaxed in April, 1962. Pushed to respond, Mayor Gordon Clinton sent a proposal to the City Council calling on the establishment of an Emergency Hotel Licensing Board. This entity would issue licenses to temporary tourist hotels only if at least 90% of their rental units were committed to transient guests during April-October of 1961. This would, theoretically, provide further sources of fair accommodation while preventing the opportunistic eviction of hotel residents in long-term occupancy of their rooms. The proposal was passed as Council Ordinance 91079 on April 17.

The Licensing Board set to work quickly separating residential hotels from potential new accommodations, though it was already under fire for its dubious legality. On May 25th, Judge W.R. Cole ruled Ordinance 91079 invalid and unconstitutional. Though shut down after barely a month of existence, the Board served its political purposes by calming public fears of rampant evictions and demonstrating the municipality's resolve to punish those landlords who acted improperly. Ultimately, the Fair housing shortage that the property owners hoped to exploit never materialized; Seattle's accommodations proved sufficient throughout the Exposition. This was due, in large part, to the effective use of unoccupied apartment projects and docked cruise ships as temporary hotels, as well as the average stay of the fairgoer being shorter than originally projected. The documents in this Digital Document Library illustrate the planning process as well as the citizen and city government reaction to housing issues during the Fair.

Though the fair was primarily administered by the non-profit private Century 21 Exposition, Incorporated, the government of Seattle was deeply involved in development and execution. Once preparations began in earnest in 1957, substantial efforts were made to integrate the planning of the municipal, state, and private entities involved. Planner Evan Dingwall, for example, simultaneously held the directorships of the Washington State World's Fair Commission and Seattle Civic Center Advisory Committee, and would later serve as general manager of Century 21 Exposition, Inc. For its part, this Advisory Committee wielded substantial influence on the design process, reflecting the long-term goal of creating a viable core of facilities for a post-Exposition Civic Center. Thanks in part to this advocacy, Seattle would inherit 400,000 square feet of permanent indoor exhibition space from the fair. In addition, the city government oversaw a number of fair-based building projects both within and beyond the fairgrounds, including the Monorail line, the International Fountain, and a 1,500-car garage along Mercer Street.

Interior photo of prototype Travel Trailer (1962)

Individual branches of municipal government also pursued a range of initiatives necessitated or provoked by Century 21. The Mayor's Office, for one, spearheaded a Downtown Beautification program that encouraged the cleanup and renovation of prominent City facilities, such as firehouses and parks. The Board of Public Works conducted oversight and licensing for building projects underway on municipal land, and so was crucial to the design and construction of fair exhibits. In 1960, $537,000 was approved to construct and install underground lighting facilities in the Century 21 site and vicinity; this involved removing approximately three and half miles of overhead pole lines. The projected influx of 10 million fairgoers prompted the Engineering Department to undertake a significant slate of improvements to the downtown transportation network, in addition to the needed incorporation of the fairgrounds into the water/ sewer utility system. Seattle City Light, finally, provided more than just the expected power to the Exposition; as a integral member of the Electric Utilities of Washington consortium, City Light played a pivotal role in developing the 'Pavilion of Electric Power,' a sizable exhibit featuring a 40-foot tall depiction of a hydroelectric dam.

Artist's rendering of possible Travel Trailer park (1962)

Controversy: Housing at the Fair

The Century 21 Exposition has generally been considered a success by later commentators, though this does not mean it occurred without incident. A principal controversy arose from the perceived 'housing crunch' expected during the fair, as millions of tourists descend upon the city and rapidly fill up existing hotels and motels. Unless extraordinary action was taken, many felt, fair visitors would be turned away without accommodation, damaging the Exposition's reputation. As the City Council took steps to respond, such as permitting the use of docked 'marine vessels' as temporary lodgings, certain residential hotel owners sought to exploit the housing shortage. With little warning, these landlords converted their buildings, which often housed people who had resided there for years, from monthly rentals to daily. Thus, prices were raised significantly, effectively 'pricing out' long-term residents in favor of the more lucrative tourist trade. Understandably angered by their 'eviction,' many wrote emotional letters to the Mayor, City Council, and the Seattle press. Though the actual numbers of residents evicted remains unclear, public indignation ignited a heated debate over what the municipal government should do in response.

Artist's rendering of interior of prototype Travel Trailer (1962)

Public concern over landlord malfeasance climaxed in April, 1962. Pushed to respond, Mayor Gordon Clinton sent a proposal to the City Council calling on the establishment of an Emergency Hotel Licensing Board. This entity would issue licenses to temporary tourist hotels only if at least 90% of their rental units were committed to transient guests during April-October of 1961. This would, theoretically, provide further sources of fair accommodation while preventing the opportunistic eviction of hotel residents in long-term occupancy of their rooms. The proposal was passed as Council Ordinance 91079 on April 17.

The Licensing Board set to work quickly separating residential hotels from potential new accommodations, though it was already under fire for its dubious legality. On May 25th, Judge W.R. Cole ruled Ordinance 91079 invalid and unconstitutional. Though shut down after barely a month of existence, the Board served its political purposes by calming public fears of rampant evictions and demonstrating the municipality's resolve to punish those landlords who acted improperly. Ultimately, the Fair housing shortage that the property owners hoped to exploit never materialized; Seattle's accommodations proved sufficient throughout the Exposition. This was due, in large part, to the effective use of unoccupied apartment projects and docked cruise ships as temporary hotels, as well as the average stay of the fairgoer being shorter than originally projected. The documents in this Digital Document Library illustrate the planning process as well as the citizen and city government reaction to housing issues during the Fair.

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Re: 1962 Seattle World Fair

Re: 1962 Seattle World Fair

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

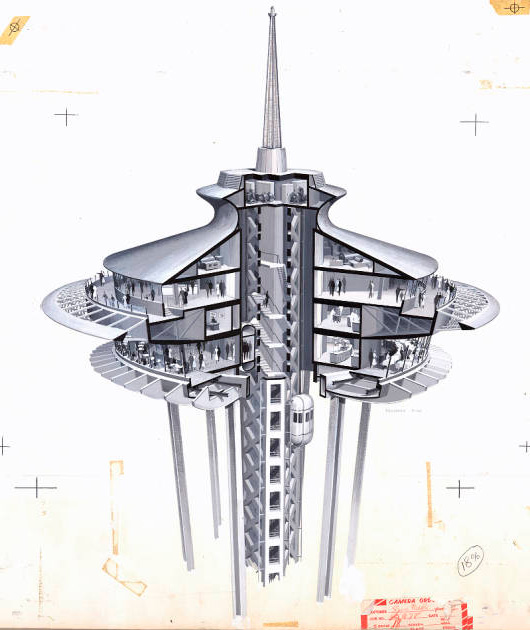

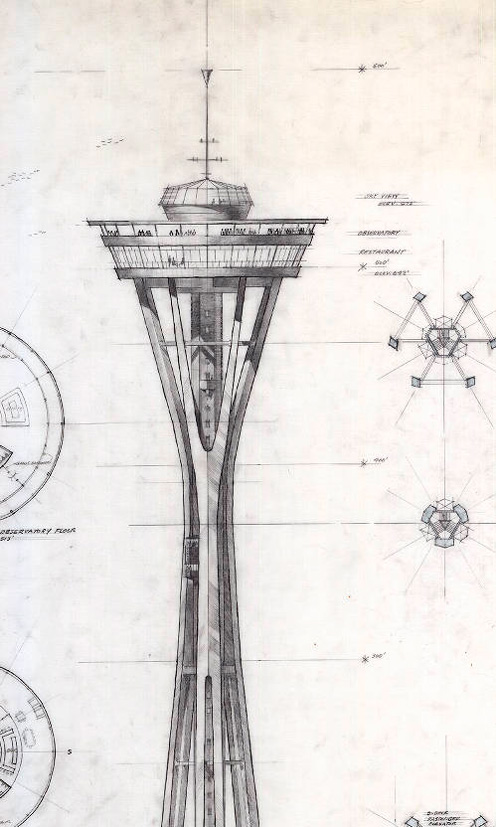

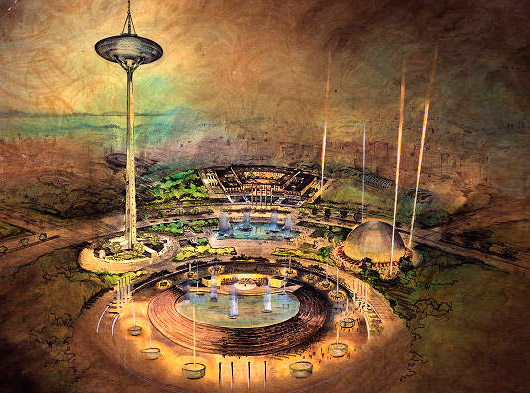

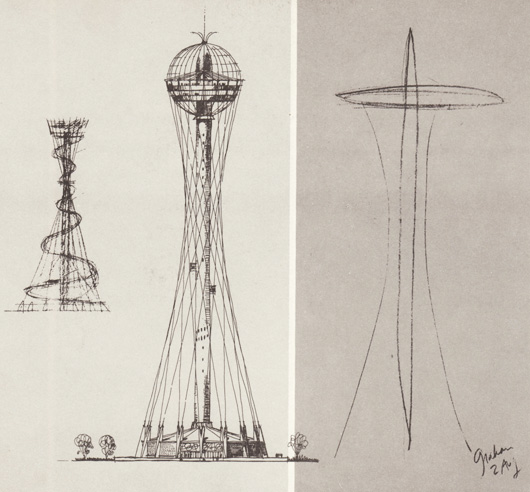

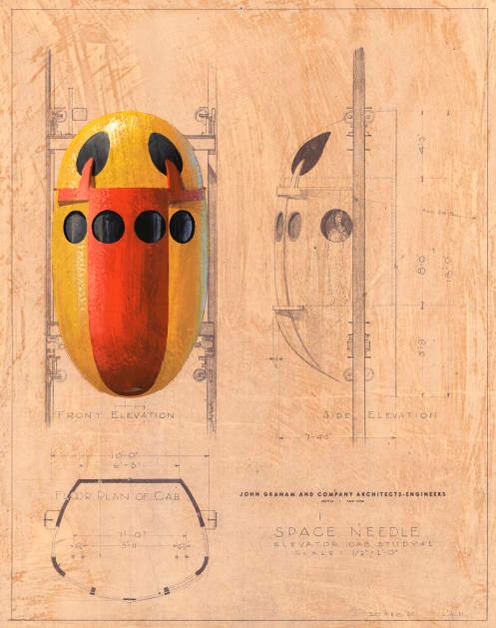

Century 21 Exposition Space Needle Design

Century 21 Exposition Space Needle Design

The Space Needle is one of the most photographed architectural monuments in Seattle. It’s very surprising how many people live in the Seattle area and have never been to the top or been informed of its intriguing history. Being that the Space Needle is such a spotlighted attraction for Seattle I believe that knowing the some of the history about it, could perhaps influence your photographs or anything relating to the monument.

These drawings show the preliminary stages of design and proposed designs that the Space Needle went through for the 1962 Worlds Fair. Edward Carlson and Victor Steinbrueck were credited for coming up with the elements of these designs

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Re: 1962 Seattle World Fair

Re: 1962 Seattle World Fair

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Re: 1962 Seattle World Fair

Re: 1962 Seattle World Fair

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Re: 1962 Seattle World Fair

Re: 1962 Seattle World Fair

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Re: 1962 Seattle World Fair

Re: 1962 Seattle World Fair

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Re: 1962 Seattle World Fair

Re: 1962 Seattle World Fair

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Seattle World's Fair. U.S. Science Exhibit. [Now Pacific Science Center]

Seattle World's Fair. U.S. Science Exhibit. [Now Pacific Science Center]

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Arches of Science Pavilion

Arches of Science Pavilion

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Century 21 / Seattle World's Fair 1962. Space Needle

Century 21 / Seattle World's Fair 1962. Space Needle

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

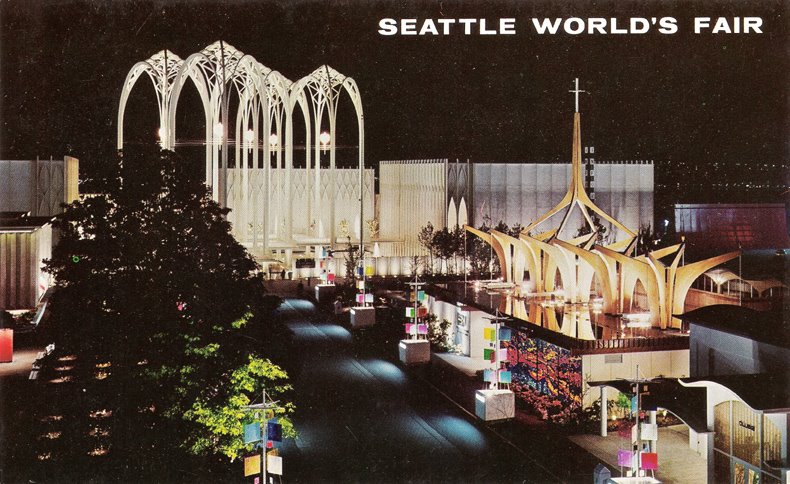

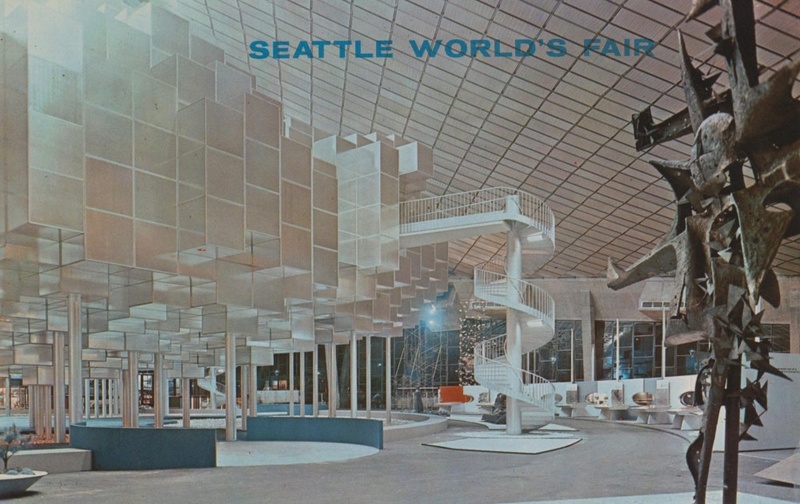

Century 21 / Seattle World's Fair. Night View of World's Fair

Century 21 / Seattle World's Fair. Night View of World's Fair

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Century 21 / Seattle World's Fair. Seattle International Fountain

Century 21 / Seattle World's Fair. Seattle International Fountain

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Century 21 / Seattle World's Fair. Alweg Monorail Train.

Century 21 / Seattle World's Fair. Alweg Monorail Train.

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Century 21 . Sky Ride, Rotor Ride and Skywheel on Gay Way.

Century 21 . Sky Ride, Rotor Ride and Skywheel on Gay Way.

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

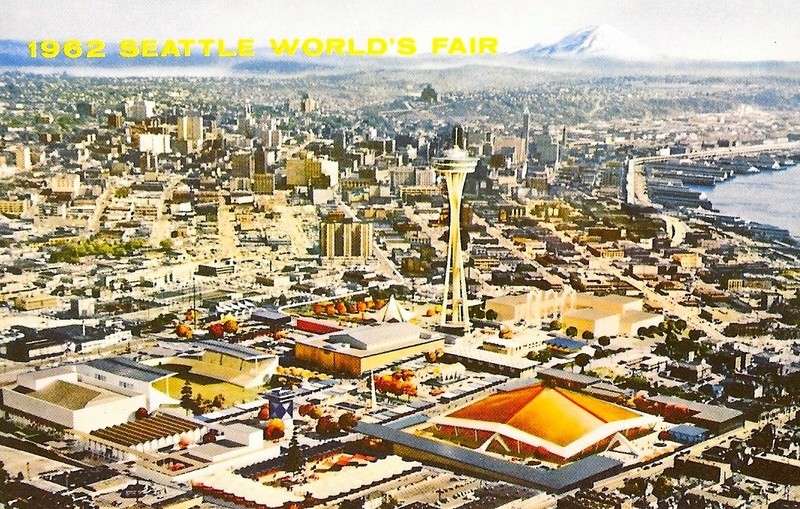

Century 21 / Seattle World's Fair. Aerial View of World's Fair

Century 21 / Seattle World's Fair. Aerial View of World's Fair

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Page 1 sur 2 • 1, 2

Sujets similaires

Sujets similaires» 1964-1965 New York World's Fair - New York

» 1962 Ford Seattle-ite XXI

» 1955 Milan Trade Fair

» Dick's drive inn - Seattle - 1954

» 1950s 1960s billboards - panneaux publicitaires en reliè des bord de route aux usa

» 1962 Ford Seattle-ite XXI

» 1955 Milan Trade Fair

» Dick's drive inn - Seattle - 1954

» 1950s 1960s billboards - panneaux publicitaires en reliè des bord de route aux usa

Traditional Kustom Hot Rod and Vintage Culture and design :: Architecture: mid century modern, Googie, Art deco :: World's Fair - Expositions universelles

Page 1 sur 2

Permission de ce forum:

Vous ne pouvez pas répondre aux sujets dans ce forum

Connexion

Connexion