1952-1954 Packard Panther and Pan American

1952-1954 Packard Panther and Pan American

1952-1954 Packard Panther and Pan American

Packard's series of Fifties two-seaters, the Panthers and Pan Americans, were strongly encouraged by a nepotist appointee of the chairman of the board: Alvan Macauley's son, Edward. Nepotism is a bad policy for running governments or corporations, and it's particularly dangerous in the car business. With automobiles, as Joe Frazer once put it, "there's so much money going out the window every day that if you're not careful, you'll lose your shirt."

What ultimately emerged as the 1954 Panther Daytona possibly began with this rendering by Packard stylist Dick Teague.

But they really didn't cost the company its shirt because they were, at best, a sideshow. Packard folk haven't much credited Ed Macauley for them, as they were largely the work of professional stylists and engineers. Nevertheless, without his enthusiasm, they probably would never have been built.

Alvan Macauley's presidency and board chairmanship dominated the great luxury-car producer through its grandest years, from the big Six of 1912 through the Twin Six of 1915, and on into the Classic era of the late Twenties and 1930s. He retired, a scion of Detroit, in 1948.

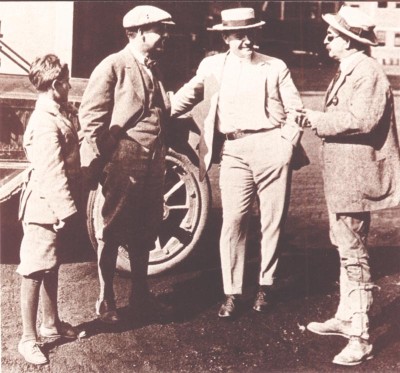

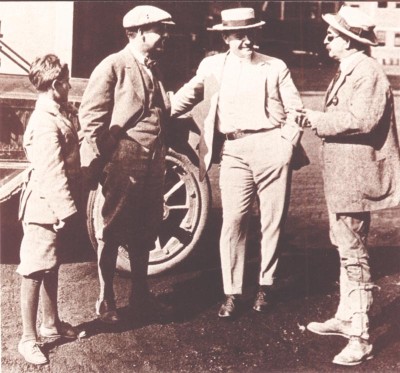

Young Ed Macauley (far left) grew up at Packard with such famous execs and racers as (1 to r) his father Alvan, Barney Oldfield, and the colorful Henry Bourne Joy.

2007 Publications International, Ltd.

2007 Publications International, Ltd.

Born into this milieu, son Edward grew up surrounded by such magnificent machines -- the veritable wonders of their age -- along with a spate of go-faster types that Packard warmly supported in its glory years. He had known the likes of Barney Oldfield and Ralph DePalma, and had admired the fast specials built with their encouragement by company chief engineer Jesse Vincent. He was also on close terms with Packard's various coachbuilders.

With all this, it was only natural that Ed Macauley would go to work for his father's firm. He first served as a salesman for the diesel engine department. Then, in January 1932, his father appointed him head of the newly formed Styling Division. Here he would remain, ostensibly in overall charge, through 1955.

"He was no designer," Ray Dietrich recalled. "He was a playboy." (This sharp attitude may have had something to do with Dietrich's not being retained as a Packard consultant after his ouster from Dietrich Inc.) But Ray Dietrich was one of the few designers who had anything negative to say about young Ed. Most of his colleagues respected him because, like many a great leader, he never overrode the final opinion of his professionals.

In Packard: A History of the Motorcar and the Company, contributing author George Hamlin described Ed Macauley as "a fine coordinator and administrator, a good manager...He had a good 'eye' for design, and was personally responsible for Packard's offering some of the finest custom bodies during the Thirties. He knew, and insisted upon, quality...was universally liked...and was always referred to as a gentleman in a field not noted for a preponderance of same."

Ed's most important accomplishment, wrote C.A. Leslie in the same book, was to "unify Packard body styling. Previously, there was no correlation between open, closed or convertible designs...Macauley [changed] all this, and eventually coordinated Packard's body styling so that phaeton, convertible, sedan or town car would each contain the same design elements."

Once installed at Packard Styling, Ed quickly appointed Count Alexis de Sakhnoffsky as a consultant. With the Count's help he fashioned a number of personal specials, and developed the line of speedsters that came to define the Classic sporty Packard in their day. Though Macauley played more of a background role after the war, the first car called "Panther" was indubitably his own.

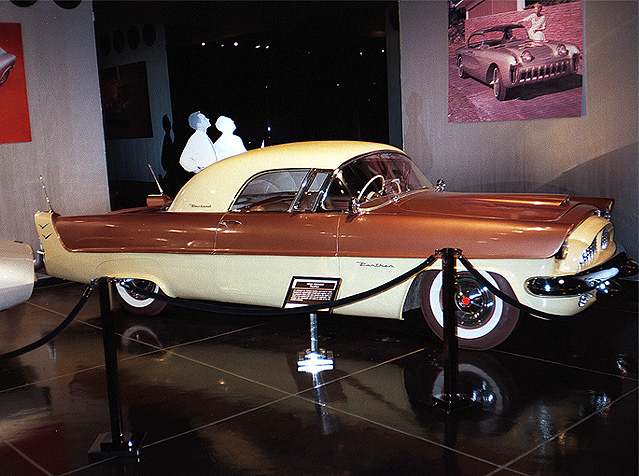

The Packard Panther was designed largely by staff designer John Reinhart. After Reinhart had conjured up Packard's all-new 1951 line, Ed Macauley asked him to help spin off a "speedster" version, continuing the firm's prewar practice of building swoopy two-seaters with bits and pieces from contemporary production models. Riding the 122-inch-wheelbase junior chassis, the first Panther was a foreshortened coupe, with a permanent hardtop fashioned from what appears to be a 1953 Patrician sedan roof.

When it first appeared in 1953, the Panther wore the current-production rear bumper, 1952 hood crest, 1951 Packard lettering on a 1952 grille, and a hood scoop borrowed from the Henney Company's own two-seat Packard, the Pan American. Painted black and bearing a partly blacked-out grille, this one-off was later given the Panther name, with big block letters on the grille. Whether it was first used here or was just a reaction to other influences is not certain, but the letters were undoubtedly of Packard origin, as we could see when we photographed the car at the Packard Club national meet last summer.

One of the faults in Reinhart's 1951 body design was its shallow greenhouse area and high sides. (For this reason, Reinhart nicknamed it the "high pockets" shell, and fought unsuccessfully with management to lower the beltline before production.) Macauley successfully disguised this on the two-seater with a broad, ribbed, chrome-plated brass applique along the lower body. It came off pretty well, but would have cost the world to implement on production cars. Also fitted were custom wheel covers bearing 1951 Patrician cloisonne center emblems. Curiously, Ed mounted a swiveling spotlight on the roof.

This is an original factory photos of Macauley's 1953 two-seat special. Swivelling roof spotlamp, disc wheel covers, shaved deck, and rear-fender dual exhausts have all been changed since.

Only one Macauley Panther was built. Although originally powered by Packard's 327-cubic-inch straight eight hooked to the firm's self-shift Ultramatic Drive, it now carries a Chrysler V-8 and TorqueFlite automatic. Several styling features have also been changed along the way. Gone are the rooftop spot, the prominent chrome highlights along the front fenders (to match the original ones at the rear), and the dual exhaust outlets ducted through, special holes under the taillights.

The enormous rear deck -- "large enough to land a Piper Cub," as Tom McCahill said of the 1959 Chevy -- was shaved in Ed Macauley's time, but now bears a conventional 1953 trunk handle. Six chrome dummy louvers have been added to the side of each front fender, while the wheel covers have been replaced by Packard/Kelsey-Hayes chrome wires.

Ed Macauley drove his Panther into the late Fifties. Though it apparently spent some time in Connecticut's former Melton Museum, its interim history is obscure.

What ultimately emerged as the 1954 Panther Daytona possibly began with this rendering by Packard stylist Dick Teague.

But they really didn't cost the company its shirt because they were, at best, a sideshow. Packard folk haven't much credited Ed Macauley for them, as they were largely the work of professional stylists and engineers. Nevertheless, without his enthusiasm, they probably would never have been built.

Alvan Macauley's presidency and board chairmanship dominated the great luxury-car producer through its grandest years, from the big Six of 1912 through the Twin Six of 1915, and on into the Classic era of the late Twenties and 1930s. He retired, a scion of Detroit, in 1948.

Young Ed Macauley (far left) grew up at Packard with such famous execs and racers as (1 to r) his father Alvan, Barney Oldfield, and the colorful Henry Bourne Joy.

2007 Publications International, Ltd.

2007 Publications International, Ltd.Born into this milieu, son Edward grew up surrounded by such magnificent machines -- the veritable wonders of their age -- along with a spate of go-faster types that Packard warmly supported in its glory years. He had known the likes of Barney Oldfield and Ralph DePalma, and had admired the fast specials built with their encouragement by company chief engineer Jesse Vincent. He was also on close terms with Packard's various coachbuilders.

With all this, it was only natural that Ed Macauley would go to work for his father's firm. He first served as a salesman for the diesel engine department. Then, in January 1932, his father appointed him head of the newly formed Styling Division. Here he would remain, ostensibly in overall charge, through 1955.

"He was no designer," Ray Dietrich recalled. "He was a playboy." (This sharp attitude may have had something to do with Dietrich's not being retained as a Packard consultant after his ouster from Dietrich Inc.) But Ray Dietrich was one of the few designers who had anything negative to say about young Ed. Most of his colleagues respected him because, like many a great leader, he never overrode the final opinion of his professionals.

In Packard: A History of the Motorcar and the Company, contributing author George Hamlin described Ed Macauley as "a fine coordinator and administrator, a good manager...He had a good 'eye' for design, and was personally responsible for Packard's offering some of the finest custom bodies during the Thirties. He knew, and insisted upon, quality...was universally liked...and was always referred to as a gentleman in a field not noted for a preponderance of same."

Ed's most important accomplishment, wrote C.A. Leslie in the same book, was to "unify Packard body styling. Previously, there was no correlation between open, closed or convertible designs...Macauley [changed] all this, and eventually coordinated Packard's body styling so that phaeton, convertible, sedan or town car would each contain the same design elements."

Once installed at Packard Styling, Ed quickly appointed Count Alexis de Sakhnoffsky as a consultant. With the Count's help he fashioned a number of personal specials, and developed the line of speedsters that came to define the Classic sporty Packard in their day. Though Macauley played more of a background role after the war, the first car called "Panther" was indubitably his own.

The Packard Panther was designed largely by staff designer John Reinhart. After Reinhart had conjured up Packard's all-new 1951 line, Ed Macauley asked him to help spin off a "speedster" version, continuing the firm's prewar practice of building swoopy two-seaters with bits and pieces from contemporary production models. Riding the 122-inch-wheelbase junior chassis, the first Panther was a foreshortened coupe, with a permanent hardtop fashioned from what appears to be a 1953 Patrician sedan roof.

When it first appeared in 1953, the Panther wore the current-production rear bumper, 1952 hood crest, 1951 Packard lettering on a 1952 grille, and a hood scoop borrowed from the Henney Company's own two-seat Packard, the Pan American. Painted black and bearing a partly blacked-out grille, this one-off was later given the Panther name, with big block letters on the grille. Whether it was first used here or was just a reaction to other influences is not certain, but the letters were undoubtedly of Packard origin, as we could see when we photographed the car at the Packard Club national meet last summer.

One of the faults in Reinhart's 1951 body design was its shallow greenhouse area and high sides. (For this reason, Reinhart nicknamed it the "high pockets" shell, and fought unsuccessfully with management to lower the beltline before production.) Macauley successfully disguised this on the two-seater with a broad, ribbed, chrome-plated brass applique along the lower body. It came off pretty well, but would have cost the world to implement on production cars. Also fitted were custom wheel covers bearing 1951 Patrician cloisonne center emblems. Curiously, Ed mounted a swiveling spotlight on the roof.

This is an original factory photos of Macauley's 1953 two-seat special. Swivelling roof spotlamp, disc wheel covers, shaved deck, and rear-fender dual exhausts have all been changed since.

Only one Macauley Panther was built. Although originally powered by Packard's 327-cubic-inch straight eight hooked to the firm's self-shift Ultramatic Drive, it now carries a Chrysler V-8 and TorqueFlite automatic. Several styling features have also been changed along the way. Gone are the rooftop spot, the prominent chrome highlights along the front fenders (to match the original ones at the rear), and the dual exhaust outlets ducted through, special holes under the taillights.

The enormous rear deck -- "large enough to land a Piper Cub," as Tom McCahill said of the 1959 Chevy -- was shaved in Ed Macauley's time, but now bears a conventional 1953 trunk handle. Six chrome dummy louvers have been added to the side of each front fender, while the wheel covers have been replaced by Packard/Kelsey-Hayes chrome wires.

Ed Macauley drove his Panther into the late Fifties. Though it apparently spent some time in Connecticut's former Melton Museum, its interim history is obscure.

Dernière édition par Predicta le Jeu 28 Sep - 11:51, édité 1 fois

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Re: 1952-1954 Packard Panther and Pan American

Re: 1952-1954 Packard Panther and Pan American

The Packard Pan American was another sporty two-seater, like the Panther. While Macauley and Reirihart were dreaming up their "speedster," Packard president Hugh Ferry had engaged the Henney Body Company, the firm's longtime supplier of hearse and ambulance bodies, to create a two-seat Packard of its own.

In those days, anybody who was anybody in Detroit had to have a sports car, if only for show. Most companies bought a Jaguar XK-120, the ne plus ultra at that time, took careful measurements, and went to work using as many off-the-shelf components as they could. Nash teamed with Donald Healey on the 1951-1954 Nash-Healey. Chevrolet readied a production two-seater called Corvette, while sister GM divisions produced a raft of Motorama specials in its image

Richard Arbib and Henney Body designed and built the chopped and channeled Pan American, which led directly to the production 1953 Caribbean.

Ford replied to Chevy with the Thunderbird for 1955, a year after Kaiser produced its sliding-door Darrin. Hudson offered the memorably ugly, slow, and unsaleable Italia, based on one of the wilder imaginings of chief stylist Frank Spring. Even Studebaker briefly toyed with the idea of a sprightly sportster, derived from its lovely "Loewy coupe." Packard was probably the firm least likely to build a production sports car, but it did turn out up to six Pan Americans, apparently with the idea of limited series production.

Designed by Richard Arbib of Henney, the first Pan American was hurriedly cobbled up from a stock 1951 Series 250 convertible for New York's International Motor Sports Show in March 1952. Chopped and channeled, it dealt once and for all with the "high pockets'" slab sides, was elegantly trimmed throughout, and wore Arbib's own rendition of Packard's traditional "ox-yoke" grille.

Henney spent just under $10,000 on the venture. Later, it tried unsuccessfully to develop a market for the car. Of course, Packard management couldn't foresee any kind of demand at the $18,000-odd they'd have to charge, so the Pan American was stillborn. It did lead to a sporty production model, however, the famous Caribbean. But that's another story.

In those days, anybody who was anybody in Detroit had to have a sports car, if only for show. Most companies bought a Jaguar XK-120, the ne plus ultra at that time, took careful measurements, and went to work using as many off-the-shelf components as they could. Nash teamed with Donald Healey on the 1951-1954 Nash-Healey. Chevrolet readied a production two-seater called Corvette, while sister GM divisions produced a raft of Motorama specials in its image

Richard Arbib and Henney Body designed and built the chopped and channeled Pan American, which led directly to the production 1953 Caribbean.

Ford replied to Chevy with the Thunderbird for 1955, a year after Kaiser produced its sliding-door Darrin. Hudson offered the memorably ugly, slow, and unsaleable Italia, based on one of the wilder imaginings of chief stylist Frank Spring. Even Studebaker briefly toyed with the idea of a sprightly sportster, derived from its lovely "Loewy coupe." Packard was probably the firm least likely to build a production sports car, but it did turn out up to six Pan Americans, apparently with the idea of limited series production.

Designed by Richard Arbib of Henney, the first Pan American was hurriedly cobbled up from a stock 1951 Series 250 convertible for New York's International Motor Sports Show in March 1952. Chopped and channeled, it dealt once and for all with the "high pockets'" slab sides, was elegantly trimmed throughout, and wore Arbib's own rendition of Packard's traditional "ox-yoke" grille.

Henney spent just under $10,000 on the venture. Later, it tried unsuccessfully to develop a market for the car. Of course, Packard management couldn't foresee any kind of demand at the $18,000-odd they'd have to charge, so the Pan American was stillborn. It did lead to a sporty production model, however, the famous Caribbean. But that's another story.

Dernière édition par Predicta le Jeu 28 Sep - 11:45, édité 1 fois

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Re: 1952-1954 Packard Panther and Pan American

Re: 1952-1954 Packard Panther and Pan American

The 1954 Panther Daytona was designed to replace the Packard Pan American. In 1953, Arbib sketched what he called a “Panther,” apparently a proposed Pan American update. Packard, meanwhile, had decided to pursue its own sports car project. The design assignment was handed to young Richard A. Teague, who by then had relieved John Reinhart as chief stylist under Ed Macauley.

What would become the 1954 Panther Daytona was, as Teague remembers, “a lunch hour production. Somebody walked into Styling one day and said, ‘Oh yeah, Teague, come up with a replacement for the Pan American.’ We didn’t have much time to work on it, and I personally built only a quarter-scale half-model in clay, which we placed against a mirror to get the full dimension.

Teague's Panther Daytona half-model was made to quarter scale.

It was originally to have been called ‘Grey Wolf II,’ in honor of the first Grey Wolf racing car of the early 1900s,” Teague continued. “But some of the grey wolves at Packard didn’t like that, so the name was changed to ‘Panther.’ Then, after a speed run at Daytona, that name was added, too.”

Another Dick Teague rendering, this time for "Grey Wolf II."

2007 Publications International, Ltd.

2007 Publications International, Ltd.

Unlike its predecessors, this new series of two-seat Packards employed bodywork of glass-reinforced plastic (GRP) instead of steel. Credit for originating the idea of GRP car bodies usually goes to designer Howard A. “Dutch” Darrin (for his one-off, 1946 Kaiser-Frazer-based convertible and the production 1954 Darrin sports car) or to GM (1953 Corvette). But few realize that Packard was talking about this as early as October 1941.

That was the month when Clyde Vandeburg of Packard Public Relations wrote a piece on the subject for Esquire magazine, accompanied by renderings of fiberglass Packards by John Reinhart and George Walker. As the firm’s rationale was potential steel shortages resulting from the defense emergency, Darrin remains the first to propose GRP as a steel replacement on grounds other than simple supply.

For Packard in 1954, building the Teague Panther in fiberglass made as much sense as it did to Chevy for the Corvette or K-F for the Kaiser-Darrin. GRP molds cost far less than steel dies, and body parts could be turned out much more rapidly. Then too, Ed Macauley had some useful outside resources as potential contractors: Creative Industries in Detroit and Mitchell-Bentley in Ionia, Michigan.

Panther Number 1 after "Grey Wolf" script was removed.

2007 Publications International, Ltd.

2007 Publications International, Ltd.

According to Leon Dixon, who carefully researched the story for Packard Magazine in 1984, Creative handled all chassis and body engineering for the Teague Panther, while Mitchell-Bentley did the final trim, including tops and interiors. Creative also made the GRP molds for the body panels. Dixon notes that these firms were a perfect team. Mitchell-Bentley had been making GM production bodies since the late 1930s, had built the experimental Packard Balboa-X of 1953, and had done all the conversion work on the production 1953-54 Caribbean. Creative had been skillfully developing special bodies for industry clients since its founding in 1950, and was well experienced with fiberglass. (Not widely known is the fact that the first DeLorean mockup was done at Creative, which is still in business today.)

Packard announced the Panther at a round of 1954 auto shows and with a special brochure, much like those that GM issued on its Motorama specials. The front end was a confusing mishmash of several design ideas, but Teague had given the car smooth, clean flanks, and cleverly blended in the “sore thumb” taillights of the production 1954 Clipper. “Functionalism is the key in the design,” said the brochure. “The traditional, classic Packard grille has been modified to afford maximum cooling. The high guideline fenders hood the headlights. The sloping clamshell hood provides unobstructed visibility.” Equally significant -- and just slightly behind GM -- was a wrapped windshield, a fairly exotic piece of glass-bending at the time.

To further establish the Panther’s sporting credentials, Packard installed the biggest engine it had: a 359-cubic-inch straight eight. On the first two examples, this was jacked up to 275 horsepower via a McCulloch centrifugal supercharger. With no modifications other than a racing windscreen, a Panther flashed through the measured mile on the sands of Daytona Beach at the highest speed ever attained by a car in its class: 131.1 mph. It was quite an achievement. Indeed, none of its rivals at the time, including Corvette, could match it.

What would become the 1954 Panther Daytona was, as Teague remembers, “a lunch hour production. Somebody walked into Styling one day and said, ‘Oh yeah, Teague, come up with a replacement for the Pan American.’ We didn’t have much time to work on it, and I personally built only a quarter-scale half-model in clay, which we placed against a mirror to get the full dimension.

Teague's Panther Daytona half-model was made to quarter scale.

It was originally to have been called ‘Grey Wolf II,’ in honor of the first Grey Wolf racing car of the early 1900s,” Teague continued. “But some of the grey wolves at Packard didn’t like that, so the name was changed to ‘Panther.’ Then, after a speed run at Daytona, that name was added, too.”

Another Dick Teague rendering, this time for "Grey Wolf II."

2007 Publications International, Ltd.

2007 Publications International, Ltd.Unlike its predecessors, this new series of two-seat Packards employed bodywork of glass-reinforced plastic (GRP) instead of steel. Credit for originating the idea of GRP car bodies usually goes to designer Howard A. “Dutch” Darrin (for his one-off, 1946 Kaiser-Frazer-based convertible and the production 1954 Darrin sports car) or to GM (1953 Corvette). But few realize that Packard was talking about this as early as October 1941.

That was the month when Clyde Vandeburg of Packard Public Relations wrote a piece on the subject for Esquire magazine, accompanied by renderings of fiberglass Packards by John Reinhart and George Walker. As the firm’s rationale was potential steel shortages resulting from the defense emergency, Darrin remains the first to propose GRP as a steel replacement on grounds other than simple supply.

For Packard in 1954, building the Teague Panther in fiberglass made as much sense as it did to Chevy for the Corvette or K-F for the Kaiser-Darrin. GRP molds cost far less than steel dies, and body parts could be turned out much more rapidly. Then too, Ed Macauley had some useful outside resources as potential contractors: Creative Industries in Detroit and Mitchell-Bentley in Ionia, Michigan.

Panther Number 1 after "Grey Wolf" script was removed.

2007 Publications International, Ltd.

2007 Publications International, Ltd.According to Leon Dixon, who carefully researched the story for Packard Magazine in 1984, Creative handled all chassis and body engineering for the Teague Panther, while Mitchell-Bentley did the final trim, including tops and interiors. Creative also made the GRP molds for the body panels. Dixon notes that these firms were a perfect team. Mitchell-Bentley had been making GM production bodies since the late 1930s, had built the experimental Packard Balboa-X of 1953, and had done all the conversion work on the production 1953-54 Caribbean. Creative had been skillfully developing special bodies for industry clients since its founding in 1950, and was well experienced with fiberglass. (Not widely known is the fact that the first DeLorean mockup was done at Creative, which is still in business today.)

Packard announced the Panther at a round of 1954 auto shows and with a special brochure, much like those that GM issued on its Motorama specials. The front end was a confusing mishmash of several design ideas, but Teague had given the car smooth, clean flanks, and cleverly blended in the “sore thumb” taillights of the production 1954 Clipper. “Functionalism is the key in the design,” said the brochure. “The traditional, classic Packard grille has been modified to afford maximum cooling. The high guideline fenders hood the headlights. The sloping clamshell hood provides unobstructed visibility.” Equally significant -- and just slightly behind GM -- was a wrapped windshield, a fairly exotic piece of glass-bending at the time.

To further establish the Panther’s sporting credentials, Packard installed the biggest engine it had: a 359-cubic-inch straight eight. On the first two examples, this was jacked up to 275 horsepower via a McCulloch centrifugal supercharger. With no modifications other than a racing windscreen, a Panther flashed through the measured mile on the sands of Daytona Beach at the highest speed ever attained by a car in its class: 131.1 mph. It was quite an achievement. Indeed, none of its rivals at the time, including Corvette, could match it.

Dernière édition par Predicta le Jeu 28 Sep - 11:43, édité 1 fois

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Re: 1952-1954 Packard Panther and Pan American

Re: 1952-1954 Packard Panther and Pan American

Packard Panther Daytona production was precluded by Packard's mounting financial problems after purchasing Studebaker, plus the very limited Fifties market for sporty domestics (even Corvette almost died in 1954). Thus, only four Daytona Panthers were built, all essentially prototypes. Mitchell-Bentley modified the last two with "cathedral" taillights and other 1955 details in a vain attempt to sell them for the new model year.

M-B also applied "Mitchell" script to one, ostensibly a gesture at self-marketing, and grafted on one experimental hardtop. Happily, all four of these cars survive today. The red example seen here is Panther #2, the Daytona speed record car.

The Packard Panther Number 2 prompted the addition of the Daytona surname after a blistering 131.1 mph speed-record run on the sands of the famous Florida beach.

Packard's legendary West Coast distributor, Earle C. Anthony, desperately wanted a production Panther, and even circulated drawings of one based on the stillborn 1957 big Packard design. But the idea never had a chance in the midst of the financial disaster that was Studebaker-Packard in those years.

Not that it was missed much, at least by its creator. "I can't stand it," Teague says of the 1954 Panther Daytona. "But then, I didn't like anything I ever did." Snorts a prominent hobby editor: "You could entitle that [car] 'Why Packard Failed.' You'd have to tie bones onto it to get the dogs to chase it."

This Packard Panther's only modification was a racing windscreen.

2007 Publications International, Ltd.

2007 Publications International, Ltd.

But the bulk of opinion is far less harsh among Packard partisans, who must, after all, be allowed a certain bias. Yet though even they admit that the front end is pretty grim, the rest of the Panther is sleek and interesting, at least in its clean, original 1954 form. And there's no doubt that if there were more than four to go around, we'd see a lengthy line of eager buyers clutching checkbooks and wads of bills. Too bad they'll never get the chance.

M-B also applied "Mitchell" script to one, ostensibly a gesture at self-marketing, and grafted on one experimental hardtop. Happily, all four of these cars survive today. The red example seen here is Panther #2, the Daytona speed record car.

The Packard Panther Number 2 prompted the addition of the Daytona surname after a blistering 131.1 mph speed-record run on the sands of the famous Florida beach.

Packard's legendary West Coast distributor, Earle C. Anthony, desperately wanted a production Panther, and even circulated drawings of one based on the stillborn 1957 big Packard design. But the idea never had a chance in the midst of the financial disaster that was Studebaker-Packard in those years.

Not that it was missed much, at least by its creator. "I can't stand it," Teague says of the 1954 Panther Daytona. "But then, I didn't like anything I ever did." Snorts a prominent hobby editor: "You could entitle that [car] 'Why Packard Failed.' You'd have to tie bones onto it to get the dogs to chase it."

This Packard Panther's only modification was a racing windscreen.

2007 Publications International, Ltd.

2007 Publications International, Ltd.But the bulk of opinion is far less harsh among Packard partisans, who must, after all, be allowed a certain bias. Yet though even they admit that the front end is pretty grim, the rest of the Panther is sleek and interesting, at least in its clean, original 1954 form. And there's no doubt that if there were more than four to go around, we'd see a lengthy line of eager buyers clutching checkbooks and wads of bills. Too bad they'll never get the chance.

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Re: 1952-1954 Packard Panther and Pan American

Re: 1952-1954 Packard Panther and Pan American

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Re: 1952-1954 Packard Panther and Pan American

Re: 1952-1954 Packard Panther and Pan American

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Re: 1952-1954 Packard Panther and Pan American

Re: 1952-1954 Packard Panther and Pan American

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Re: 1952-1954 Packard Panther and Pan American

Re: 1952-1954 Packard Panther and Pan American

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Re: 1952-1954 Packard Panther and Pan American

Re: 1952-1954 Packard Panther and Pan American

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Re: 1952-1954 Packard Panther and Pan American

Re: 1952-1954 Packard Panther and Pan American

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Re: 1952-1954 Packard Panther and Pan American

Re: 1952-1954 Packard Panther and Pan American

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Sujets similaires

Sujets similaires» Les Incontournables accessoires pour nos anciennes - hot rod, custom and classic accessories and parts

» Packard custom & mild custom

» 1952 Edward Macauley's Packard Special Speedster

» Corbillards - Cars for the funeral

» PACKARD BELL 532 Plastic Ivory CLOCK/TUBE RADIO - 1954

» Packard custom & mild custom

» 1952 Edward Macauley's Packard Special Speedster

» Corbillards - Cars for the funeral

» PACKARD BELL 532 Plastic Ivory CLOCK/TUBE RADIO - 1954

Permission de ce forum:

Vous ne pouvez pas répondre aux sujets dans ce forum

Connexion

Connexion