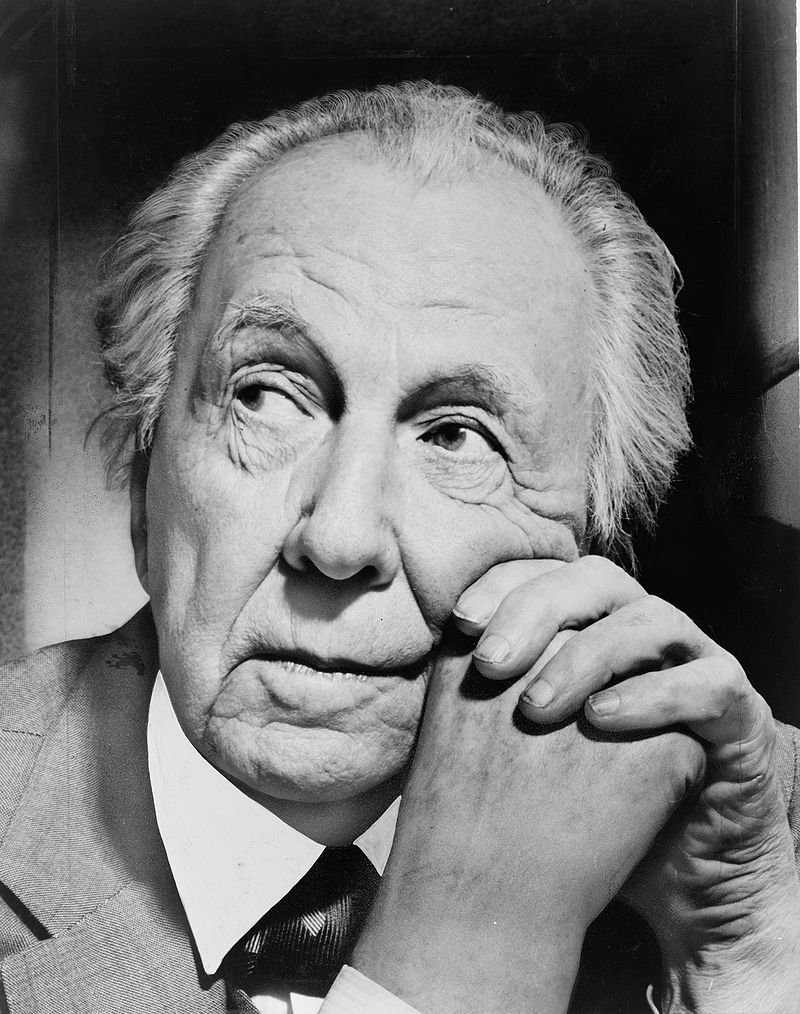

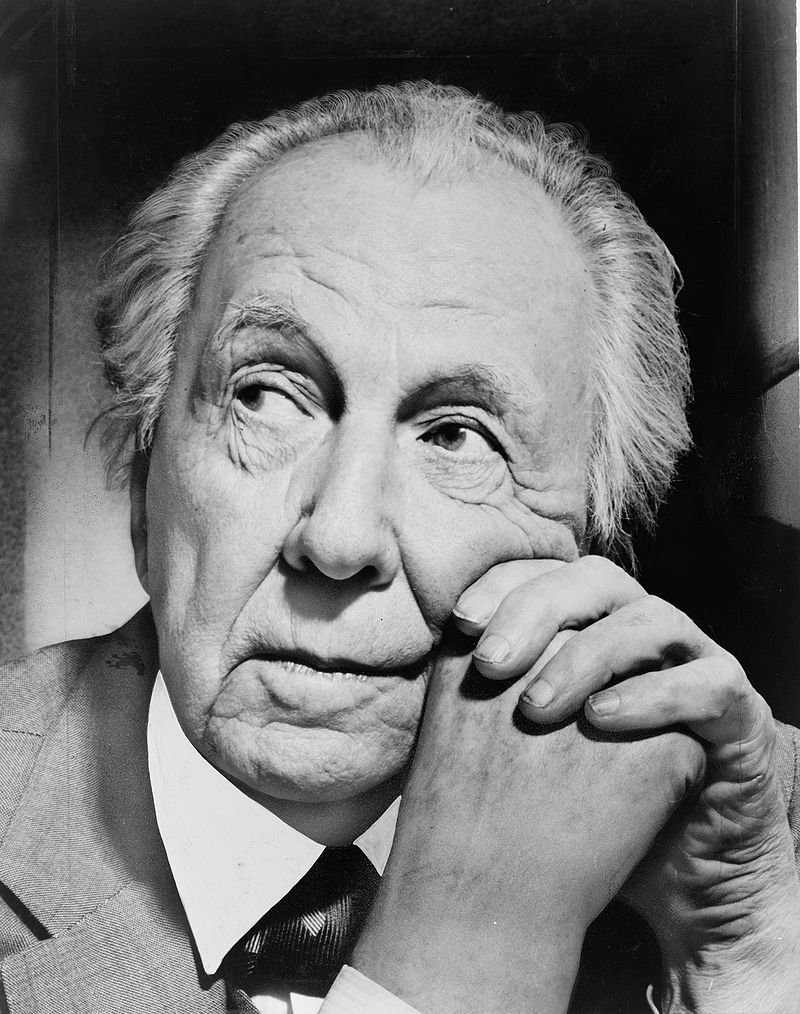

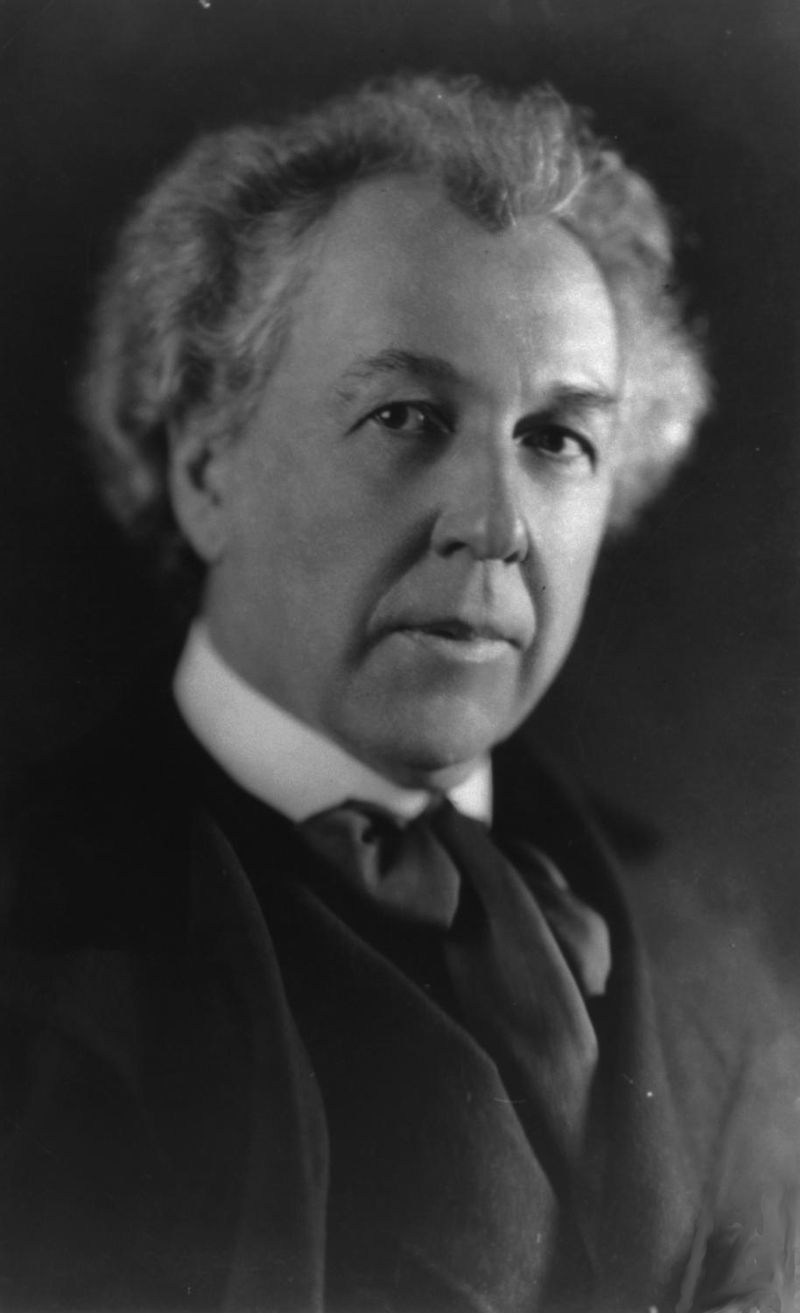

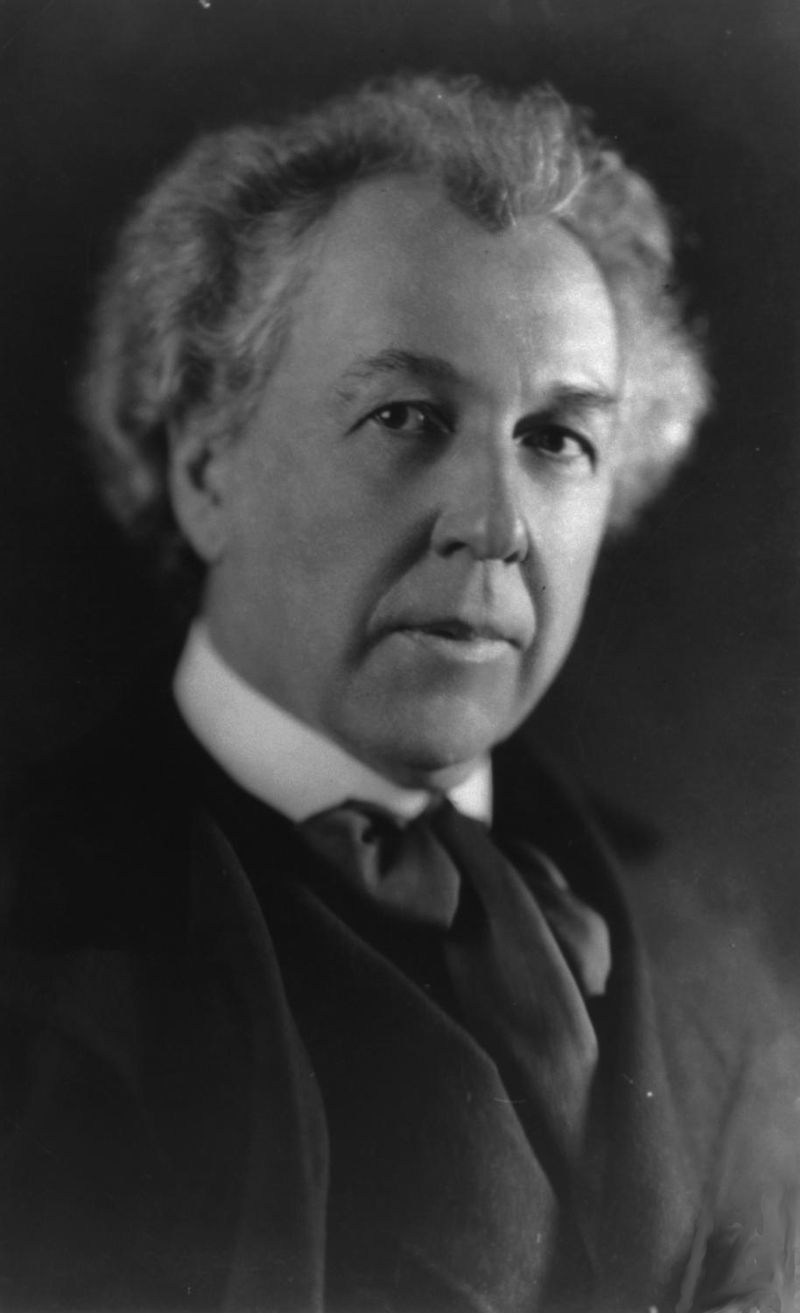

Frank Lloyd Wright - 1867 / 1959

Traditional Kustom Hot Rod and Vintage Culture and design :: Architects & Designers - Mid Century Modern - Vintage 50 - 70 - MCM

Page 1 sur 1

Frank Lloyd Wright - 1867 / 1959

Frank Lloyd Wright - 1867 / 1959

Frank Lloyd Wright, né le 8 juin 1867 à Richland Center dans le Wisconsin et mort le 9 avril 1959 à Phoenix en Arizona, est un architecte et concepteur américain.

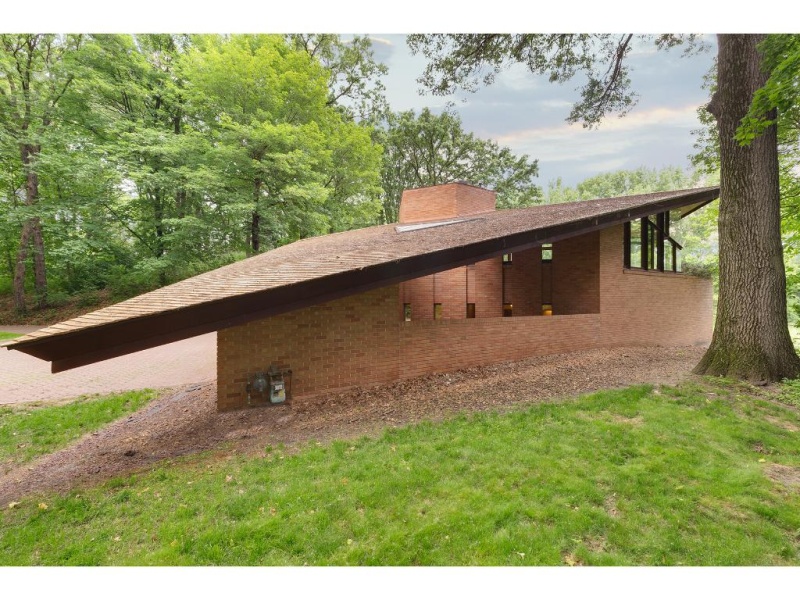

Il est l’auteur de plus de quatre cents projets réalisés, musées, stations-service, tours d’habitation, hôtels, églises, ateliers, mais principalement des maisons qui ont fait sa renommée. Il est notamment le principal protagoniste du style Prairie et le concepteur des maisons usoniennes, petites habitations en harmonie avec l’environnement où elles sont construites. En 1991, il a été reconnu par l’Institut des architectes américains comme le plus grand architecte américain de l’histoire1.

Premières années

Article connexe : École de Chicago (architecture).

Frank Lloyd Wright est né en 1867 dans la petite ville de Richland Centre au Wisconsin sous le nom de Frank Lincoln Wright. Après le divorce de ses parents – William Carey Wright (1825-1904) et Anna Lloyd Jones (1839-1923) – en 1885, il change le nom Lincoln pour Lloyd, en l’honneur de sa mère, dont il devient le soutien financier, ainsi que de ses deux sœurs.

En 1887, Wright s'installe à Chicago2, en quête d’un emploi. La ville se remettait alors de l’incendie dévastateur de 1871 et devait composer avec un accroissement galopant de sa population. Wright finit par se dénicher un emploi de dessinateur technique pour la firme de l’architecte Joseph Lyman Silsbee. Plusieurs dessinateurs et architectes travaillent déjà pour Silsbee, dont Cecil Corwin, George W. Maher et George Grant Elmslie. Wright se lie d'amitié avec Corwin, qui l'héberge durant un temps.

Attiré par une architecture plus moderne que celle que pratiquait Silsbee, il se joint bientôt au cabinet des architectes Adler et Sullivan, représentant l'école de Chicago. Sullivan prend le jeune apprenti sous son aile. En dépit des divergences entre eux, Wright demeurera toujours reconnaissant et attaché à celui qui lui enseigne les rudiments du métier.

Maison et studio Frank Lloyd Wright (1898) à Oak Park, près de Chicago

Maison et studio Frank Lloyd Wright (1898) à Oak Park, près de Chicago

En 1889, Wright épouse Catherine Lee Tobin (1871-1959), dont il aura six enfants. Avec l’aide de Sullivan qui lui consent un prêt de 5 000 $, Wright achète un lot à Oak Park, en banlieue de Chicago. C’est là, à l’intersection des avenues Forest et Chicago, qu'il construit sa première maison (Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio) dont le style, avec un grand puits central apportant vie et lumière à l'habitation, annonce ses futures réalisations. Wright demeure à l'emploi de la firme Adler et Sullivan durant six ans et collabore principalement à des projets de maisons individuelles. C'est là qu'il acquiert l'essentiel de sa formation et une partie de son inspiration dans ce domaine. Mais une séparation brutale se produit bientôt, car Wright conçoit des maisons pour son propre compte pendant ses heures libres, afin de combler ses besoins financiers. Il contrevient ainsi aux clauses de son contrat qui lui interdisent tout projet en dehors de la firme. Frank Lloyd Wright démissionna.

Il est l’auteur de plus de quatre cents projets réalisés, musées, stations-service, tours d’habitation, hôtels, églises, ateliers, mais principalement des maisons qui ont fait sa renommée. Il est notamment le principal protagoniste du style Prairie et le concepteur des maisons usoniennes, petites habitations en harmonie avec l’environnement où elles sont construites. En 1991, il a été reconnu par l’Institut des architectes américains comme le plus grand architecte américain de l’histoire1.

Premières années

Article connexe : École de Chicago (architecture).

Frank Lloyd Wright est né en 1867 dans la petite ville de Richland Centre au Wisconsin sous le nom de Frank Lincoln Wright. Après le divorce de ses parents – William Carey Wright (1825-1904) et Anna Lloyd Jones (1839-1923) – en 1885, il change le nom Lincoln pour Lloyd, en l’honneur de sa mère, dont il devient le soutien financier, ainsi que de ses deux sœurs.

En 1887, Wright s'installe à Chicago2, en quête d’un emploi. La ville se remettait alors de l’incendie dévastateur de 1871 et devait composer avec un accroissement galopant de sa population. Wright finit par se dénicher un emploi de dessinateur technique pour la firme de l’architecte Joseph Lyman Silsbee. Plusieurs dessinateurs et architectes travaillent déjà pour Silsbee, dont Cecil Corwin, George W. Maher et George Grant Elmslie. Wright se lie d'amitié avec Corwin, qui l'héberge durant un temps.

Attiré par une architecture plus moderne que celle que pratiquait Silsbee, il se joint bientôt au cabinet des architectes Adler et Sullivan, représentant l'école de Chicago. Sullivan prend le jeune apprenti sous son aile. En dépit des divergences entre eux, Wright demeurera toujours reconnaissant et attaché à celui qui lui enseigne les rudiments du métier.

Maison et studio Frank Lloyd Wright (1898) à Oak Park, près de Chicago

Maison et studio Frank Lloyd Wright (1898) à Oak Park, près de Chicago

En 1889, Wright épouse Catherine Lee Tobin (1871-1959), dont il aura six enfants. Avec l’aide de Sullivan qui lui consent un prêt de 5 000 $, Wright achète un lot à Oak Park, en banlieue de Chicago. C’est là, à l’intersection des avenues Forest et Chicago, qu'il construit sa première maison (Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio) dont le style, avec un grand puits central apportant vie et lumière à l'habitation, annonce ses futures réalisations. Wright demeure à l'emploi de la firme Adler et Sullivan durant six ans et collabore principalement à des projets de maisons individuelles. C'est là qu'il acquiert l'essentiel de sa formation et une partie de son inspiration dans ce domaine. Mais une séparation brutale se produit bientôt, car Wright conçoit des maisons pour son propre compte pendant ses heures libres, afin de combler ses besoins financiers. Il contrevient ainsi aux clauses de son contrat qui lui interdisent tout projet en dehors de la firme. Frank Lloyd Wright démissionna.

Dernière édition par Predicta le Sam 9 Avr - 12:34, édité 1 fois

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Re: Frank Lloyd Wright - 1867 / 1959

Re: Frank Lloyd Wright - 1867 / 1959

En 1893, Wright découvre l'architecture japonaise à l'exposition colombienne de Chicago. C'est le palais Katsura, reconstitution d'un temple shinto, qui l'avait le plus impressionné et qui influencera durablement son style. Wright fera par la suite quelques voyages au Japon où il obtiendra même des commandes, dont l'Hôtel impérial à Tōkyō, construit en 1923.

Wright s'installe à son compte, toujours à Chicago, après son départ de la firme de Sullivan. Il fait alors la rencontre de jeunes architectes, dont Dwight H. Perkins, qui donneront bientôt naissance au style Prairie : constructions basses, élimination des cloisons inutiles, aires ouvertes, pivot central avec une cheminée massive maçonnée — surmontée d’un manteau large et bas, et autour de laquelle s'organise la vie de famille —, forte horizontalité (à l'image des vastes étendues des prairies), larges toitures basses qui se prolongent au-delà des murs, bandeaux de fenêtres, souvent agrémentées de vitraux. Le style, exemplifié à son meilleur par Wright, introduit notamment le principe d'aire ouverte, abondamment éclairée par des rangées de fenêtres, lien entre l'intérieur et l'environnement extérieur qui témoigne de l'influence de l'architecture japonaise sur Wright. Ces principes étaient alors très novateurs en occident.

Wright signe bientôt une première commande indépendante : ce sera la maison Winslow, où il met déjà en application des principes du style Prairie. Durant les années 1890, il expérimente de nouveaux matériaux et de nouvelles formes, notamment dans sa propre maison à Oak Park, comme la brique et l'horizontalité des volumes. Les bâtiments qu'il dessine n'offrent toutefois pas toujours de style très personnel, Wright devant se plier aux exigences de sa clientèle afin d'établir sa pratique. Il conçoit donc des maisons dans les styles prisés de l'époque (Tudor, revêtements de bardeaux, tourelles, fenêtres en mansarde).

En 1894, il rencontre l'architecte Burnham (1846-1912) qui avait été impressionné par la maison Winslow. Wright refuse sa proposition d'aller étudier l'architecture classique pour quatre années à l'école des beaux-arts de Paris — prestigieuse école d'architecture de l'époque —, puis deux années à Rome : « J'aime mieux être libre et rater mon coup, et être sot, que d'être lié à quelques succès de routine. Je n'y vois pas de liberté… voilà tout. »3. Wright préfère poursuivre sa propre voie vers la modernité, au sein de l'école de Chicago.

Par la suite, en 1898, Wright ouvre sa propre agence à Oak Park afin de se rapprocher de sa famille. Il en profite pour modifier sa maison et ajouter de nouvelles chambres pour ses nombreux enfants. Il construit également un studio de deux étages où il expérimente une structure octogonale et un balcon suspendu. Sur sa cheminée, il fait graver cette inscription : Truth is life. Good friend, around these hearth-stones speak no evil word of any creature (La vérité est la vie. Bon ami, autour des pierres de ce foyer, ne médis d'aucune créature

Wright perçoit les pièces d'un bâtiment comme des organes autonomes qui constituent un corps cohérent. Il pousse l'analogie avec le monde vivant jusqu'à prétendre que la construction doit représenter la croissance d'un être vivant. Cela explique la haine que Wright nourrissait vis-à-vis des grandes villes, notamment Chicago. Cette haine le poussa à ne construire que de très rares (mais notables) bâtiments dans de grandes agglomérations. Il s'intéressera davantage à des projets de maisons individuelles, construites en harmonie avec le site.

La Robie House construite entre 1906-1909, à Chicago.

À partir de 1897, son style se révèle, avec les « maisons de la prairie » (Prairie Houses) dont sa maison d'Oak Park est un précurseur; ce sont des pavillons d’un seul tenant ou en plusieurs parties reliées entre elles, dont Wright soigne particulièrement l'intégration au paysage par le biais de l'horizontalité. Il essaie également de tenir compte des contraintes que le climat continental de la région impose, multipliant les différences de hauteur des plafonds de manière à éclairer et à ventiler les pièces. Il introduit également un enchaînement plus fluide et plus ouvert des pièces, en opposition à la structure rigide de l'architecture victorienne, tout en respectant la fonction de chacune d'elles. Ces innovations passent par l'utilisation d'une combinaison de matériaux traditionnels (la pierre pour les façades et les sols) et novateurs pour l'époque : béton, acier qui servent de support à des claire-voies, des toits débordants, des terrasses en encorbellement ou de grandes baies. Le mobilier et l'éclairage électrique sont souvent intégrés au bâtiment. Les luminaires sont camouflés par des grilles dont les jeux d'ombre rappellent ceux du soleil à travers les arbres. Il en va de même des vitraux, typiques de l'art déco, qui tamisent et colorent la lumière sans l'obscurcir.

Wright se positionne alors en rupture avec l'architecture classique européenne. Il s'intéresse à définir un style qu'il qualifie d'organique, inspiré pour une part de son maître Sullivan, et qu'il estime pouvoir devenir un fondement neuf de la culture américaine. Dans cet idéal qui ne recherche pas spécialement à imiter la nature, mais qui s'en inspire, la forme des parties de la maison doit découler de leurs fonctions, tandis que forme et fonction ne doivent faire qu'un.

En 1904, Frank Lloyd Wright dessine le Larkin Building à Buffalo qu'il organise autour d'un grand puits central éclairé par le haut et sur lequel donnent les pièces de chaque étage. L'immeuble s'ouvre donc vers l'intérieur et ménage une grande salle commune en son cœur. En utilisant la pierre et la brique, en découpant des plans horizontaux, Wright refuse la standardisation des immeubles.

La même année, il offre ses services à la congrégation religieuse unitarienne d'Oak Park, dont l'église vient d’être détruite par un incendie. Wright travaille sur le projet de 1905 à 1908. Le bâtiment, construit en béton armé, est considéré comme une de ses œuvres maîtresses et influencera notablement le milieu de l'architecture moderniste.

D'autres réalisations marquantes de Wright à cette époque sont la Robie House à Chicago et la Coonley House (en) à Riverside dans l'Illinois. La maison de Frederick Robie, avec ses toitures à larges pans inclinés en porte-à-faux et l'organisation originale de l'espace intérieur, marque une rupture avec les maisons de style victorien encore courantes à l'époque. La salle à dîner et le salon forment pratiquement une seule longue pièce en continu, démarqués seulement par le foyer central, aménagé un peu en contrebas du plancher. Trois garages préfigurent déjà l'envahissement de l'automobile ! La maison est surélevée, procurant vue, lumière et intimité aux occupants, tout en conférant une impression de grandeur et de majesté à la demeure. Une maquette de la maison fut placée à l'entrée de l’exposition rétrospective qui fut consacrée à Frank Lloyd Wright en 1941 au Musée d'art moderne de New York.

Wright s'installe à son compte, toujours à Chicago, après son départ de la firme de Sullivan. Il fait alors la rencontre de jeunes architectes, dont Dwight H. Perkins, qui donneront bientôt naissance au style Prairie : constructions basses, élimination des cloisons inutiles, aires ouvertes, pivot central avec une cheminée massive maçonnée — surmontée d’un manteau large et bas, et autour de laquelle s'organise la vie de famille —, forte horizontalité (à l'image des vastes étendues des prairies), larges toitures basses qui se prolongent au-delà des murs, bandeaux de fenêtres, souvent agrémentées de vitraux. Le style, exemplifié à son meilleur par Wright, introduit notamment le principe d'aire ouverte, abondamment éclairée par des rangées de fenêtres, lien entre l'intérieur et l'environnement extérieur qui témoigne de l'influence de l'architecture japonaise sur Wright. Ces principes étaient alors très novateurs en occident.

Wright signe bientôt une première commande indépendante : ce sera la maison Winslow, où il met déjà en application des principes du style Prairie. Durant les années 1890, il expérimente de nouveaux matériaux et de nouvelles formes, notamment dans sa propre maison à Oak Park, comme la brique et l'horizontalité des volumes. Les bâtiments qu'il dessine n'offrent toutefois pas toujours de style très personnel, Wright devant se plier aux exigences de sa clientèle afin d'établir sa pratique. Il conçoit donc des maisons dans les styles prisés de l'époque (Tudor, revêtements de bardeaux, tourelles, fenêtres en mansarde).

En 1894, il rencontre l'architecte Burnham (1846-1912) qui avait été impressionné par la maison Winslow. Wright refuse sa proposition d'aller étudier l'architecture classique pour quatre années à l'école des beaux-arts de Paris — prestigieuse école d'architecture de l'époque —, puis deux années à Rome : « J'aime mieux être libre et rater mon coup, et être sot, que d'être lié à quelques succès de routine. Je n'y vois pas de liberté… voilà tout. »3. Wright préfère poursuivre sa propre voie vers la modernité, au sein de l'école de Chicago.

Par la suite, en 1898, Wright ouvre sa propre agence à Oak Park afin de se rapprocher de sa famille. Il en profite pour modifier sa maison et ajouter de nouvelles chambres pour ses nombreux enfants. Il construit également un studio de deux étages où il expérimente une structure octogonale et un balcon suspendu. Sur sa cheminée, il fait graver cette inscription : Truth is life. Good friend, around these hearth-stones speak no evil word of any creature (La vérité est la vie. Bon ami, autour des pierres de ce foyer, ne médis d'aucune créature

Wright perçoit les pièces d'un bâtiment comme des organes autonomes qui constituent un corps cohérent. Il pousse l'analogie avec le monde vivant jusqu'à prétendre que la construction doit représenter la croissance d'un être vivant. Cela explique la haine que Wright nourrissait vis-à-vis des grandes villes, notamment Chicago. Cette haine le poussa à ne construire que de très rares (mais notables) bâtiments dans de grandes agglomérations. Il s'intéressera davantage à des projets de maisons individuelles, construites en harmonie avec le site.

La Robie House construite entre 1906-1909, à Chicago.

À partir de 1897, son style se révèle, avec les « maisons de la prairie » (Prairie Houses) dont sa maison d'Oak Park est un précurseur; ce sont des pavillons d’un seul tenant ou en plusieurs parties reliées entre elles, dont Wright soigne particulièrement l'intégration au paysage par le biais de l'horizontalité. Il essaie également de tenir compte des contraintes que le climat continental de la région impose, multipliant les différences de hauteur des plafonds de manière à éclairer et à ventiler les pièces. Il introduit également un enchaînement plus fluide et plus ouvert des pièces, en opposition à la structure rigide de l'architecture victorienne, tout en respectant la fonction de chacune d'elles. Ces innovations passent par l'utilisation d'une combinaison de matériaux traditionnels (la pierre pour les façades et les sols) et novateurs pour l'époque : béton, acier qui servent de support à des claire-voies, des toits débordants, des terrasses en encorbellement ou de grandes baies. Le mobilier et l'éclairage électrique sont souvent intégrés au bâtiment. Les luminaires sont camouflés par des grilles dont les jeux d'ombre rappellent ceux du soleil à travers les arbres. Il en va de même des vitraux, typiques de l'art déco, qui tamisent et colorent la lumière sans l'obscurcir.

Wright se positionne alors en rupture avec l'architecture classique européenne. Il s'intéresse à définir un style qu'il qualifie d'organique, inspiré pour une part de son maître Sullivan, et qu'il estime pouvoir devenir un fondement neuf de la culture américaine. Dans cet idéal qui ne recherche pas spécialement à imiter la nature, mais qui s'en inspire, la forme des parties de la maison doit découler de leurs fonctions, tandis que forme et fonction ne doivent faire qu'un.

En 1904, Frank Lloyd Wright dessine le Larkin Building à Buffalo qu'il organise autour d'un grand puits central éclairé par le haut et sur lequel donnent les pièces de chaque étage. L'immeuble s'ouvre donc vers l'intérieur et ménage une grande salle commune en son cœur. En utilisant la pierre et la brique, en découpant des plans horizontaux, Wright refuse la standardisation des immeubles.

La même année, il offre ses services à la congrégation religieuse unitarienne d'Oak Park, dont l'église vient d’être détruite par un incendie. Wright travaille sur le projet de 1905 à 1908. Le bâtiment, construit en béton armé, est considéré comme une de ses œuvres maîtresses et influencera notablement le milieu de l'architecture moderniste.

D'autres réalisations marquantes de Wright à cette époque sont la Robie House à Chicago et la Coonley House (en) à Riverside dans l'Illinois. La maison de Frederick Robie, avec ses toitures à larges pans inclinés en porte-à-faux et l'organisation originale de l'espace intérieur, marque une rupture avec les maisons de style victorien encore courantes à l'époque. La salle à dîner et le salon forment pratiquement une seule longue pièce en continu, démarqués seulement par le foyer central, aménagé un peu en contrebas du plancher. Trois garages préfigurent déjà l'envahissement de l'automobile ! La maison est surélevée, procurant vue, lumière et intimité aux occupants, tout en conférant une impression de grandeur et de majesté à la demeure. Une maquette de la maison fut placée à l'entrée de l’exposition rétrospective qui fut consacrée à Frank Lloyd Wright en 1941 au Musée d'art moderne de New York.

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Re: Frank Lloyd Wright - 1867 / 1959

Re: Frank Lloyd Wright - 1867 / 1959

En 1909, Wright vit une période trouble et a le sentiment d'être parvenu à ses limites. Lassé de sa vie conjugale, en proie à des questionnements sur sa pratique, il part s'installer en Europe. Il abandonne au passage sa première femme et ses enfants, tout en emmenant la femme de l'un de ses clients, Mamah Borthwick Cheney, dont il était tombé amoureux. De ce fait, il provoque un scandale qui faillit ruiner sa carrière, sans compter son train de vie fastueux qui lui vaut d'être perpétuellement endetté et assailli par ses créanciers.

En Europe, Wright visite l'Italie. Il fréquente et influence les architectes d'avant-garde en Autriche, en Allemagne et aux Pays-Bas, dont Walter Gropius et Mies van der Rohe (qui ont fondé le Bauhaus). Il publie également un portfolio en 1910 grâce à Ernst Wasmuth qui fera connaître son œuvre. Ce recueil, connu sous le nom de Wasmuth portfolio et publié en deux volumes, contient plus de cent lithographies de ses projets. La même année, il expose certaines de ses œuvres à Berlin.

En 1911, il retourne aux États-Unis et s'installe dans le Wisconsin, où il fonde la communauté unitarienne de Spring Green. Il y construit une série de bâtiments à la fois communautaires, domestiques et agricoles sur un terrain offert par sa mère, et baptise l'ensemble Studio Taliesin, du nom du poète Taliesin dans la mythologie celtique. C'est là qu'il s'installe avec Mamah. Il démarre là une seconde carrière.

Mais le 15 août 1914, dans un accès de folie à la suite de son licenciement, un employé domestique du nom de Julian Carlton, met le feu au domaine et assassine sept personnes à coups de hache, dont Mamah Cheney. Wright surmonte cette douloureuse épreuve et reconstruit le domaine qui sera de nouveau détruit par un incendie le 22 avril 1925. Le domaine, encore une fois reconstruit, a été reconnu comme site patrimonial en 1960.

Entretemps, Wright épouse Miriam Noel en 1923, mariage de courte durée en raison de la dépendance de Noel à la morphine. Wright rencontre alors Olga (Olgivanna) Lazovich Hinzenburg avec qui il s'installe à Taliesin et qu'il épousera en 1928. Toute cette période est marquée par des déboires financiers et par la raréfaction des commandes. Il ne retrouvera véritablement son élan que durant les années trente.

Quand arrive la crise de 1929, Wright n'a plus de travail à Chicago. Comme beaucoup de ses confrères, il doit faire face à une période de récession. Il part alors pour Phoenix avec ce qui lui reste de son agence, pensant ouvrir à Taliesin West, une école d'architecture pour subvenir à ses besoins. Comme tous les Américains, Wright semble très marqué par la crise de 1929, qui reste encore aujourd'hui une date charnière dans l'histoire de ce pays.

Cette crise a été engendrée par l'artificialité de la spéculation boursière, mais c'est aussi une crise plus profonde de la terre et de la main-d'œuvre agricole. La crise de 1929 amène un repli identitaire de l'Amérique, auquel Wright n'échappe pas. Cette période marque un tournant dans son œuvre. Wright en tant qu'architecte ressent le besoin de se repositionner par rapport à la société et aux valeurs américaines. Comme beaucoup d’Américains de l'époque, il participe à cet idéal de vie nomade sur les routes et de voyages à travers les différents États. Dans cette période de remise en cause des idées sur l'architecture et sur la place même de l'architecte dans la société, Wright tente de formuler un nouveau rôle pour l'architecte. Il lui incombe désormais de restructurer l'ordre social américain.

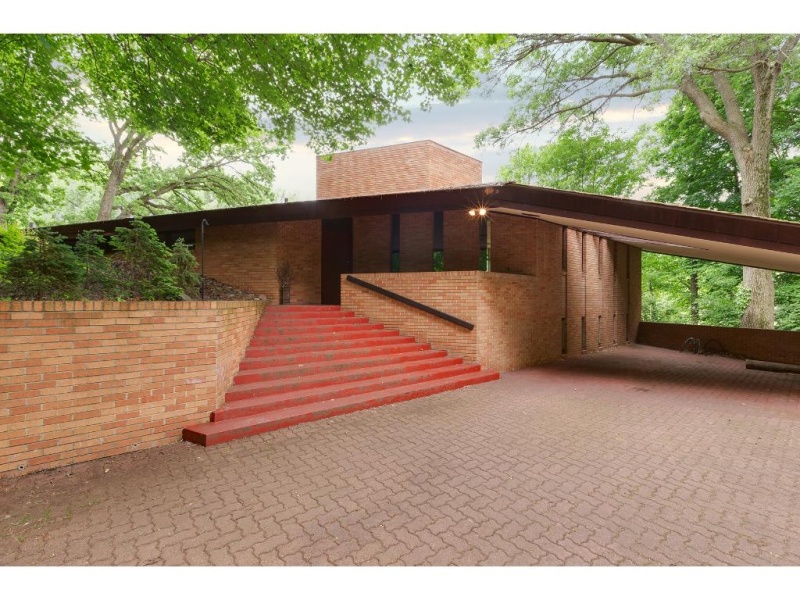

Hollyhock House, Los Angeles

En 1928, apparaît le terme « Usonie », qui désigne pour Wright l'idéal démocratique vers lequel doit tendre l'Amérique. Ce terme définit pour lui la construction de maisons individuelles abordables en grande série.

Taliesin Fellowship s'inscrivait dans cette optique d'esprit communautaire de Wright et de son enseignement. Le domaine incluait l'atelier de Wright, une ferme, des habitations, des appartements, des salles d'archives, des jardins et aménagements extérieurs, des salons de musique et de spectacle. Wright y accueillit plusieurs architectes dont Rudolf Schindler et Richard Neutra. Cette école a donné naissance à plus de soixante-dix projets.

Après la tragédie de Taliesin, en 1914, Wright reçoit une commande pour l'Hôtel impérial à Tōkyō qui lui procure l'occasion de séjours prolongés au Japon, pays à l'architecture singulière qui l'inspire grandement. Il rapporte également de là-bas plusieurs objets d’art, estampes, rouleaux, brocards de soie, dont il fera même le commerce. La réalisation de l'hôtel contribuera à un certain retour en faveur de Wright lorsque l'établissement résista au tremblement de terre de 1923, ce qui souligna les qualités de concepteur de l'architecte.

Durant les années vingt, Wright développe un concept de construction à base de blocs de béton ouvragé qui évoque l'ornementation des temples Maya. Ce procédé s'appelait textile block system5 ou construction en blocs tissés6, ornés de motifs ou ajourés. Wright cherche ainsi à conférer ses lettres de noblesse à un matériau jugé ingrat. Au lieu de peindre le ciment, il préfère lui laisser sa couleur naturelle, créant ainsi une continuité visuelle entre l'intérieur et l'extérieur.

Il expérimente ce nouveau concept, en 1916, avec la commande d'Aline Barnsdall, une riche héritière installée en Californie. Wright rompt cependant avec un principe qui lui est cher – un édifice doit émaner du site sur lequel il est construit –, car le terrain n'est pas encore acheté. De fait, Wright doit remanier ses plans pour les adapter à la colline de vingt hectares près d'Hollywood choisie par sa cliente. La maison, construite un peu comme un temple, rappelle en effet l'architecture maya. Cependant, le résultat ne convainc ni l'architecte ni la cliente. Pour Wright, il s'agissait d'un projet de transition qui dégénéra en poursuites et qu'Aline Barnsdall n'habita que peu d’années avant de faire don de la maison Hollyhock (en) à la ville en 1927.

En revanche, plusieurs maisons sont construites en Californie sur ce modèle, avec davantage de succès : la maison Millard (en) à (Pasadena), la maison Storer (en) à West Hollywood, la maison Samuel Freeman (en) à Hollywood (où la dialectique entre le dedans et le dehors, chère à Wright, est particulièrement réussie) et la maison Ennis à Los Angeles.

Wright développe son style, s'inspirant de formes géométriques, comme le cercle, le carré, le triangle, le rectangle ou l'hexagone. Il varie l'utilisation des matériaux, préférablement locaux, les méthodes de construction, les couleurs et les textures. Il affirme son souci de concevoir ses maisons en fonction du site où elles sont construites. Il joue avec les éléments naturels du paysage, l'eau, les rochers, les arbres, la végétation, les reliefs, allant souvent jusqu'à incorporer l'aménagement paysager dans les plans qu'il remet à ses clients. « En faisant de la nature le thème sous-jacent de toute sa création, il se distinguait des chefs de file de l'architecture moderne qui s'efforçaient d'élaborer une architecture représentative de l'ère de l'industrie et de la machine7. »

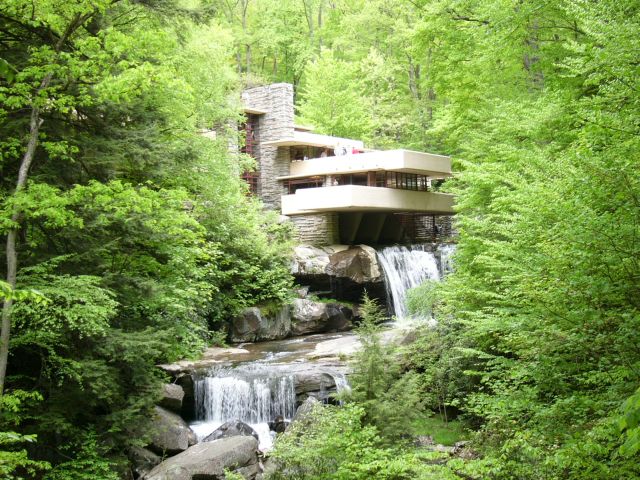

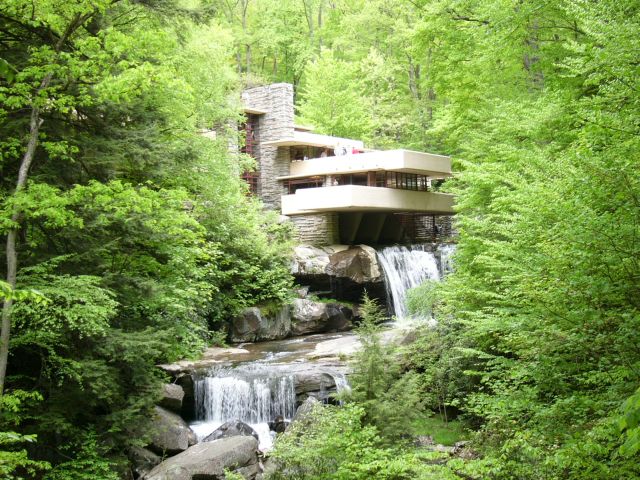

Fallingwater house (ou Maison sur la cascade), Pennsylvanie (1936)

L'exemple le plus notoire de cette approche est celui de la Maison sur la cascade (Fallingwater house) qu'il conçoit en 1935 à l'âge de soixante-huit ans. Construite directement sur le rocher où Edgar Kauffman, propriétaire, aimait pique-niquer, la maison offre une superposition de balcons en porte-à-faux surplombant la rivière attenante. Les angles sont arrondis pour mieux refléter les formes naturelles environnantes. Un escalier mène à une petite plateforme directement au-dessus de la rivière. Cet authentique chef-d'œuvre attire l'attention sur Wright, lui vaut à nouveau l'intérêt des milieux de l'architecture et relance sa carrière d'architecte. Ses années les plus fructueuses s'annoncent pour lui.

Nombreux sont ceux qui ont considéré la Fallingwater house comme l'un des exemples les plus représentatifs de l'architecture organique où l'homme et la nature sont étroitement liés. Dans cette œuvre architecturale, Franck Lloyd Wright a été précurseur en utilisant le liège comme revêtement décoratif et technique pour le sol et le mur. Dans les pièces d'eau de la chambre du propriétaire, comme dans celles des invités, le liège parcourt le sol et les murs et donne à l'ensemble une impression à la fois feutrée et terreuse. Il se fournissait auprès de la société Robinson, au Portugal, désormais disparue. Le savoir-faire a été repris par la société française Cork design, dont l’une des gammes porte le nom en son honneur.

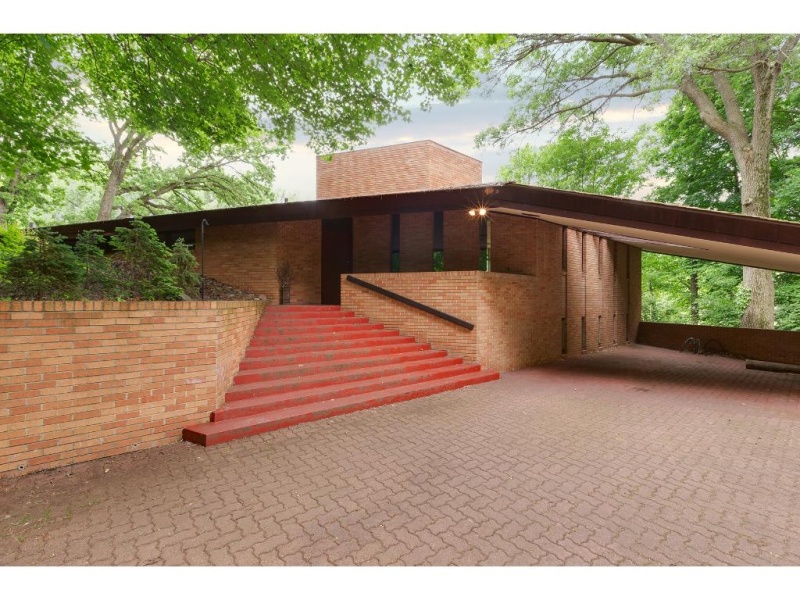

En 1934, il commence une série de maisons dites « usoniennes » (« Usonian Homes »). Ce sont, comme la Malcolm Willey house, de petites maisons économiques se caractérisant pour la plupart par un motif en L, une dalle de béton sans fondation, intégrant un système de chauffage radiant (une innovation de Wright), par des toits plats sans grenier et par de nouveaux procédés de construction des murs. Au lieu d'un garage, un simple abri pour les voitures, afin de réduire les coûts. Les maisons usoniennes étaient destinées à la classe moyenne et conçues de manière pratique avec de petites cuisines, de petites chambres, un salon ouvert autour du foyer et du mobilier intégré. Jusqu'en 1937, il construit un peu moins d'une soixantaine de ces maisons, adoptant au fur et à mesure des techniques diversifiées.

La Seconde Guerre mondiale entraîne un ralentissement des activités de Wright, qui reprennent rapidement à la fin des hostilités. À plus de quatre-vingts ans, l'architecte se retrouve à la tête d'une importante agence avec plus de cinquante assistants afin de répondre à la demande. Wright maintient la discipline avec fermeté et se réserve les projets de prestige, tout en demeurant attaché à la conception de maisons. Il accueille chaque client avec déférence, bien que la conduite du projet conduise quelquefois à des désaccords et à des brouilles, Wright aimant imposer ses idées.

Wright sera également appelé à travailler sur des projets de plus grande envergure, comme la Price Tower, gratte-ciel de dix-neuf étages construit à Bartlesville (Oklahoma) en 1956. La réalisation la plus connue de Frank Lloyd Wright demeure toutefois le musée Guggenheim à New York et inauguré en 1959. Sa conception unique s'articule autour d'un immense puits de lumière sur toute la hauteur de l'immeuble et d'une rampe en colimaçon. Le visiteur accède au dernier étage en ascenseur et emprunte ensuite la rampe en pente douce continue pour visiter les expositions jusqu'au rez-de-chaussée.

Le Kalita Humphreys Theater à Dallas (Texas) est le dernier projet de Wright, avant sa mort en 1959, à Phoenix en Arizona, des suites d'une complication chirurgicale. Il était âgé de 91 ans.

En Europe, Wright visite l'Italie. Il fréquente et influence les architectes d'avant-garde en Autriche, en Allemagne et aux Pays-Bas, dont Walter Gropius et Mies van der Rohe (qui ont fondé le Bauhaus). Il publie également un portfolio en 1910 grâce à Ernst Wasmuth qui fera connaître son œuvre. Ce recueil, connu sous le nom de Wasmuth portfolio et publié en deux volumes, contient plus de cent lithographies de ses projets. La même année, il expose certaines de ses œuvres à Berlin.

En 1911, il retourne aux États-Unis et s'installe dans le Wisconsin, où il fonde la communauté unitarienne de Spring Green. Il y construit une série de bâtiments à la fois communautaires, domestiques et agricoles sur un terrain offert par sa mère, et baptise l'ensemble Studio Taliesin, du nom du poète Taliesin dans la mythologie celtique. C'est là qu'il s'installe avec Mamah. Il démarre là une seconde carrière.

Mais le 15 août 1914, dans un accès de folie à la suite de son licenciement, un employé domestique du nom de Julian Carlton, met le feu au domaine et assassine sept personnes à coups de hache, dont Mamah Cheney. Wright surmonte cette douloureuse épreuve et reconstruit le domaine qui sera de nouveau détruit par un incendie le 22 avril 1925. Le domaine, encore une fois reconstruit, a été reconnu comme site patrimonial en 1960.

Entretemps, Wright épouse Miriam Noel en 1923, mariage de courte durée en raison de la dépendance de Noel à la morphine. Wright rencontre alors Olga (Olgivanna) Lazovich Hinzenburg avec qui il s'installe à Taliesin et qu'il épousera en 1928. Toute cette période est marquée par des déboires financiers et par la raréfaction des commandes. Il ne retrouvera véritablement son élan que durant les années trente.

Quand arrive la crise de 1929, Wright n'a plus de travail à Chicago. Comme beaucoup de ses confrères, il doit faire face à une période de récession. Il part alors pour Phoenix avec ce qui lui reste de son agence, pensant ouvrir à Taliesin West, une école d'architecture pour subvenir à ses besoins. Comme tous les Américains, Wright semble très marqué par la crise de 1929, qui reste encore aujourd'hui une date charnière dans l'histoire de ce pays.

Cette crise a été engendrée par l'artificialité de la spéculation boursière, mais c'est aussi une crise plus profonde de la terre et de la main-d'œuvre agricole. La crise de 1929 amène un repli identitaire de l'Amérique, auquel Wright n'échappe pas. Cette période marque un tournant dans son œuvre. Wright en tant qu'architecte ressent le besoin de se repositionner par rapport à la société et aux valeurs américaines. Comme beaucoup d’Américains de l'époque, il participe à cet idéal de vie nomade sur les routes et de voyages à travers les différents États. Dans cette période de remise en cause des idées sur l'architecture et sur la place même de l'architecte dans la société, Wright tente de formuler un nouveau rôle pour l'architecte. Il lui incombe désormais de restructurer l'ordre social américain.

Hollyhock House, Los Angeles

En 1928, apparaît le terme « Usonie », qui désigne pour Wright l'idéal démocratique vers lequel doit tendre l'Amérique. Ce terme définit pour lui la construction de maisons individuelles abordables en grande série.

Taliesin Fellowship s'inscrivait dans cette optique d'esprit communautaire de Wright et de son enseignement. Le domaine incluait l'atelier de Wright, une ferme, des habitations, des appartements, des salles d'archives, des jardins et aménagements extérieurs, des salons de musique et de spectacle. Wright y accueillit plusieurs architectes dont Rudolf Schindler et Richard Neutra. Cette école a donné naissance à plus de soixante-dix projets.

Après la tragédie de Taliesin, en 1914, Wright reçoit une commande pour l'Hôtel impérial à Tōkyō qui lui procure l'occasion de séjours prolongés au Japon, pays à l'architecture singulière qui l'inspire grandement. Il rapporte également de là-bas plusieurs objets d’art, estampes, rouleaux, brocards de soie, dont il fera même le commerce. La réalisation de l'hôtel contribuera à un certain retour en faveur de Wright lorsque l'établissement résista au tremblement de terre de 1923, ce qui souligna les qualités de concepteur de l'architecte.

Durant les années vingt, Wright développe un concept de construction à base de blocs de béton ouvragé qui évoque l'ornementation des temples Maya. Ce procédé s'appelait textile block system5 ou construction en blocs tissés6, ornés de motifs ou ajourés. Wright cherche ainsi à conférer ses lettres de noblesse à un matériau jugé ingrat. Au lieu de peindre le ciment, il préfère lui laisser sa couleur naturelle, créant ainsi une continuité visuelle entre l'intérieur et l'extérieur.

Il expérimente ce nouveau concept, en 1916, avec la commande d'Aline Barnsdall, une riche héritière installée en Californie. Wright rompt cependant avec un principe qui lui est cher – un édifice doit émaner du site sur lequel il est construit –, car le terrain n'est pas encore acheté. De fait, Wright doit remanier ses plans pour les adapter à la colline de vingt hectares près d'Hollywood choisie par sa cliente. La maison, construite un peu comme un temple, rappelle en effet l'architecture maya. Cependant, le résultat ne convainc ni l'architecte ni la cliente. Pour Wright, il s'agissait d'un projet de transition qui dégénéra en poursuites et qu'Aline Barnsdall n'habita que peu d’années avant de faire don de la maison Hollyhock (en) à la ville en 1927.

En revanche, plusieurs maisons sont construites en Californie sur ce modèle, avec davantage de succès : la maison Millard (en) à (Pasadena), la maison Storer (en) à West Hollywood, la maison Samuel Freeman (en) à Hollywood (où la dialectique entre le dedans et le dehors, chère à Wright, est particulièrement réussie) et la maison Ennis à Los Angeles.

Wright développe son style, s'inspirant de formes géométriques, comme le cercle, le carré, le triangle, le rectangle ou l'hexagone. Il varie l'utilisation des matériaux, préférablement locaux, les méthodes de construction, les couleurs et les textures. Il affirme son souci de concevoir ses maisons en fonction du site où elles sont construites. Il joue avec les éléments naturels du paysage, l'eau, les rochers, les arbres, la végétation, les reliefs, allant souvent jusqu'à incorporer l'aménagement paysager dans les plans qu'il remet à ses clients. « En faisant de la nature le thème sous-jacent de toute sa création, il se distinguait des chefs de file de l'architecture moderne qui s'efforçaient d'élaborer une architecture représentative de l'ère de l'industrie et de la machine7. »

Fallingwater house (ou Maison sur la cascade), Pennsylvanie (1936)

L'exemple le plus notoire de cette approche est celui de la Maison sur la cascade (Fallingwater house) qu'il conçoit en 1935 à l'âge de soixante-huit ans. Construite directement sur le rocher où Edgar Kauffman, propriétaire, aimait pique-niquer, la maison offre une superposition de balcons en porte-à-faux surplombant la rivière attenante. Les angles sont arrondis pour mieux refléter les formes naturelles environnantes. Un escalier mène à une petite plateforme directement au-dessus de la rivière. Cet authentique chef-d'œuvre attire l'attention sur Wright, lui vaut à nouveau l'intérêt des milieux de l'architecture et relance sa carrière d'architecte. Ses années les plus fructueuses s'annoncent pour lui.

Nombreux sont ceux qui ont considéré la Fallingwater house comme l'un des exemples les plus représentatifs de l'architecture organique où l'homme et la nature sont étroitement liés. Dans cette œuvre architecturale, Franck Lloyd Wright a été précurseur en utilisant le liège comme revêtement décoratif et technique pour le sol et le mur. Dans les pièces d'eau de la chambre du propriétaire, comme dans celles des invités, le liège parcourt le sol et les murs et donne à l'ensemble une impression à la fois feutrée et terreuse. Il se fournissait auprès de la société Robinson, au Portugal, désormais disparue. Le savoir-faire a été repris par la société française Cork design, dont l’une des gammes porte le nom en son honneur.

En 1934, il commence une série de maisons dites « usoniennes » (« Usonian Homes »). Ce sont, comme la Malcolm Willey house, de petites maisons économiques se caractérisant pour la plupart par un motif en L, une dalle de béton sans fondation, intégrant un système de chauffage radiant (une innovation de Wright), par des toits plats sans grenier et par de nouveaux procédés de construction des murs. Au lieu d'un garage, un simple abri pour les voitures, afin de réduire les coûts. Les maisons usoniennes étaient destinées à la classe moyenne et conçues de manière pratique avec de petites cuisines, de petites chambres, un salon ouvert autour du foyer et du mobilier intégré. Jusqu'en 1937, il construit un peu moins d'une soixantaine de ces maisons, adoptant au fur et à mesure des techniques diversifiées.

La Seconde Guerre mondiale entraîne un ralentissement des activités de Wright, qui reprennent rapidement à la fin des hostilités. À plus de quatre-vingts ans, l'architecte se retrouve à la tête d'une importante agence avec plus de cinquante assistants afin de répondre à la demande. Wright maintient la discipline avec fermeté et se réserve les projets de prestige, tout en demeurant attaché à la conception de maisons. Il accueille chaque client avec déférence, bien que la conduite du projet conduise quelquefois à des désaccords et à des brouilles, Wright aimant imposer ses idées.

Wright sera également appelé à travailler sur des projets de plus grande envergure, comme la Price Tower, gratte-ciel de dix-neuf étages construit à Bartlesville (Oklahoma) en 1956. La réalisation la plus connue de Frank Lloyd Wright demeure toutefois le musée Guggenheim à New York et inauguré en 1959. Sa conception unique s'articule autour d'un immense puits de lumière sur toute la hauteur de l'immeuble et d'une rampe en colimaçon. Le visiteur accède au dernier étage en ascenseur et emprunte ensuite la rampe en pente douce continue pour visiter les expositions jusqu'au rez-de-chaussée.

Le Kalita Humphreys Theater à Dallas (Texas) est le dernier projet de Wright, avant sa mort en 1959, à Phoenix en Arizona, des suites d'une complication chirurgicale. Il était âgé de 91 ans.

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Re: Frank Lloyd Wright - 1867 / 1959

Re: Frank Lloyd Wright - 1867 / 1959

Wright a aussi rédigé plusieurs ouvrages sur l'architecture. Son œuvre a profondément marqué le développement de l'architecture contemporaine, aux États-Unis et en Europe. Il a influencé un grand nombre d'architectes, dont plusieurs ont étudié avec lui, et par la même occasion divers courants artistiques, dont l'expressionnisme.

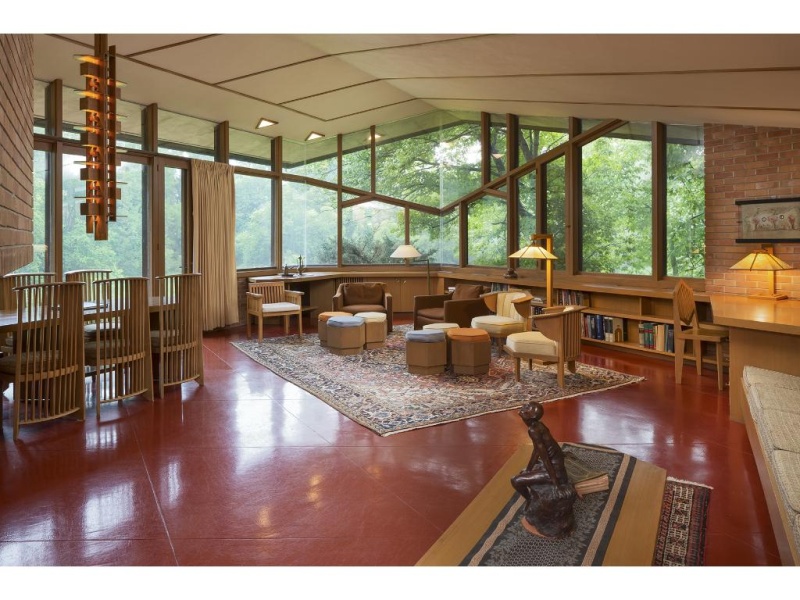

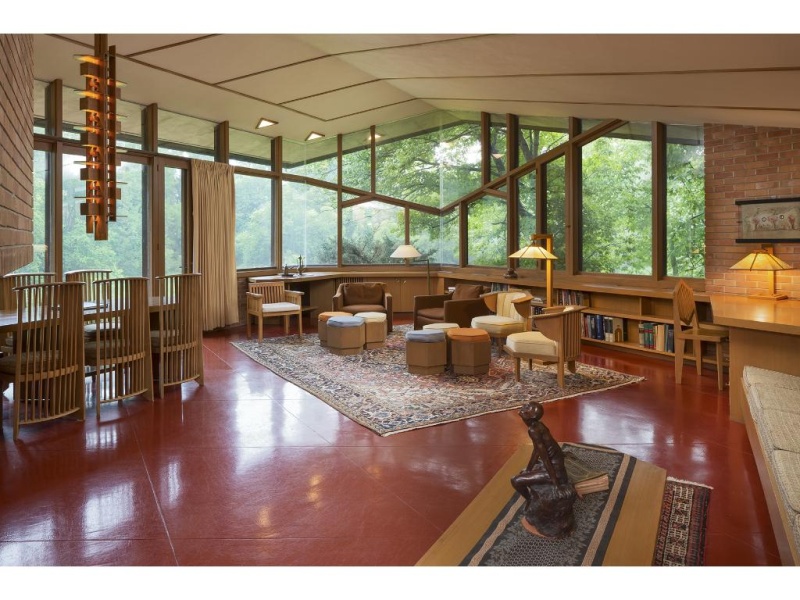

Il fut l'un des premiers architectes à intégrer l'aménagement intérieur dans ses réalisations : mobilier, tapis, fenêtres, vitraux, portes, tables, chaises, dispositifs d’éclairage et éléments décoratifs. Tous ces éléments sur mesure faisaient partie intégrante de la conception qu'il présentait à son client.

À cela s'ajoute son exploration autant des formes (ellipses, rectangles imbriqués, cercles, octogones, hémicycles pour mieux laisser entrer la lumière du soleil, etc.) que des matériaux (acier, brique, bois, verre et ciment, dont un ciment rouge indien qu'il affectionnait pour les revêtements de sol). Wright marie ces éléments avec imagination, toujours dans le souci de proposer des espaces lumineux et chaleureux, en influençant le style de vie de ses occupants de la manière la plus heureuse qui soit. Wright s'accordait ainsi à l'air du temps, qui voyait la disparition progressive des domestiques et le besoin d'organiser plus efficacement la vie familiale, avec des aires ouvertes pour faciliter le soin aux enfants et l'accueil des invités.

Le plus grand mérite de Wright se résume sans doute dans le fait que les espaces de vie qu'il concevait s'adressaient à tous les types de clients, qu'ils soient fortunés ou non, et qu'ils modifiaient leur relation à l'habitat. « Ses clients observaient que leur résidence avait changé et simplifié leur vie, les avait sensibilisés au paysage et au monde naturels qui les entourait8. »

Au total, Wright a dessiné près de 800 projets, dont environ la moitié a été réalisée. Plusieurs archives de Frank Lloyd Wright sont conservées à l'Institut d'art de Chicago. Une fondation à son nom existe également ; elle est installée à Taliesin West.

Il fait partie des personnalités dont John Dos Passos a écrit une courte biographie, au sein de sa trilogie U.S.A..

Il fut l'un des premiers architectes à intégrer l'aménagement intérieur dans ses réalisations : mobilier, tapis, fenêtres, vitraux, portes, tables, chaises, dispositifs d’éclairage et éléments décoratifs. Tous ces éléments sur mesure faisaient partie intégrante de la conception qu'il présentait à son client.

À cela s'ajoute son exploration autant des formes (ellipses, rectangles imbriqués, cercles, octogones, hémicycles pour mieux laisser entrer la lumière du soleil, etc.) que des matériaux (acier, brique, bois, verre et ciment, dont un ciment rouge indien qu'il affectionnait pour les revêtements de sol). Wright marie ces éléments avec imagination, toujours dans le souci de proposer des espaces lumineux et chaleureux, en influençant le style de vie de ses occupants de la manière la plus heureuse qui soit. Wright s'accordait ainsi à l'air du temps, qui voyait la disparition progressive des domestiques et le besoin d'organiser plus efficacement la vie familiale, avec des aires ouvertes pour faciliter le soin aux enfants et l'accueil des invités.

Le plus grand mérite de Wright se résume sans doute dans le fait que les espaces de vie qu'il concevait s'adressaient à tous les types de clients, qu'ils soient fortunés ou non, et qu'ils modifiaient leur relation à l'habitat. « Ses clients observaient que leur résidence avait changé et simplifié leur vie, les avait sensibilisés au paysage et au monde naturels qui les entourait8. »

Au total, Wright a dessiné près de 800 projets, dont environ la moitié a été réalisée. Plusieurs archives de Frank Lloyd Wright sont conservées à l'Institut d'art de Chicago. Une fondation à son nom existe également ; elle est installée à Taliesin West.

Il fait partie des personnalités dont John Dos Passos a écrit une courte biographie, au sein de sa trilogie U.S.A..

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Re: Frank Lloyd Wright - 1867 / 1959

Re: Frank Lloyd Wright - 1867 / 1959

Frank Lloyd Wright (born Frank Lincoln Wright, June 8, 1867 – April 9, 1959) was an American architect, interior designer, writer, and educator, who designed more than 1,000 structures, 532 of which were completed. Wright believed in designing structures that were in harmony with humanity and its environment, a philosophy he called organic architecture. This philosophy was best exemplified by Fallingwater (1935), which has been called "the best all-time work of American architecture".[1] Wright was a leader of the Prairie School movement of architecture and developed the concept of the Usonian home, his unique vision for urban planning in the United States. His creative period spanned more than 70 years.

His work includes original and innovative examples of many building types, including offices, churches, schools, skyscrapers, hotels, and museums. Wright also designed many of the interior elements of his buildings, such as the furniture and stained glass. Wright wrote 20 books and many articles and was a popular lecturer in the United States and in Europe. His colorful personal life often made headlines, most notably for the 1914 fire and murders at his Taliesin studio. Already well known during his lifetime, Wright was recognized in 1991 by the American Institute of Architects as "the greatest American architect of all time".[1]

Frank Lloyd Wright was born Frank Lincoln Wright in the farming town of Richland Center, Wisconsin, United States, in 1867. His father, William Carey Wright (1825–1904), was a locally admired orator, music teacher, occasional lawyer, and itinerant minister. William Wright met and married Anna Lloyd Jones (1838/39 – 1923), a county school teacher, the previous year when he was employed as the superintendent of schools for Richland County. Originally from Massachusetts, William Wright had been a Baptist minister, but he later joined his wife's family in the Unitarian faith. Anna was a member of the large, prosperous and well-known Lloyd Jones family of Unitarians, who had emigrated from Wales to Spring Green, Wisconsin. One of Anna's brothers was Jenkin Lloyd Jones, who would become an important figure in the spread of the Unitarian faith in the Western United States. Both of Wright's parents were strong-willed individuals with idiosyncratic interests that they passed on to him. According to his biography, his mother declared when she was expecting that her first child would grow up to build beautiful buildings. She decorated his nursery with engravings of English cathedrals torn from a periodical to encourage the infant's ambition.[2] The family moved to Weymouth, Massachusetts in 1870 for William to minister a small congregation.

Wright's home in Oak Park, Illinois

In 1876, Anna visited the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia and saw an exhibit of educational blocks created by Friedrich Wilhelm August Fröbel. The blocks, known as Froebel Gifts, were the foundation of his innovative kindergarten curriculum. A trained teacher, Anna was excited by the program and bought a set of blocks for her family. Young Wright spent much time playing with the blocks. These were geometrically shaped and could be assembled in various combinations to form three-dimensional compositions. This is how Wright described, in his autobiography, the influence of these exercises on his approach to design: "For several years I sat at the little Kindergarten table-top ... and played ... with the cube, the sphere and the triangle—these smooth wooden maple blocks ... All are in my fingers to this day ..."[3] Many of his buildings are notable for their geometrical clarity.

The Wright family struggled financially in Weymouth and returned to Spring Green, Wisconsin, where the supportive Lloyd Jones clan could help William find employment. They settled in Madison, where William taught music lessons and served as the secretary to the newly formed Unitarian society. Although William was a distant parent, he shared his love of music, especially the works of Johann Sebastian Bach, with his children.

Soon after Wright turned 14, his parents separated. Anna had been unhappy for some time with William's inability to provide for his family and asked him to leave. The divorce was finalized in 1885 after William sued Anna for lack of physical affection. William left Wisconsin after the divorce and Wright claimed he never saw his father again.[4] At this time he changed his middle name from Lincoln to Lloyd in honor of his mother's family, the Lloyd Joneses. As the only male left in the family, Wright assumed financial responsibility for his mother and two sisters.

Wright attended Madison High School, but there is no evidence he ever graduated.[5] He was admitted to the University of Wisconsin–Madison as a special student in 1886. There he joined Phi Delta Theta fraternity,[6] took classes part-time for two semesters, and worked with a professor of civil engineering, Allan D. Conover.[7] . In 1887, Wright left the school without taking a degree (although he was granted an honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts from the University in 1955) and arrived in Chicago in search of employment. As a result of the devastating Great Chicago Fire of 1871 and recent population boom, new development was plentiful in the city. He later recalled that his first impressions of Chicago were that of grimy neighborhoods, crowded streets, and disappointing architecture, yet he was determined to find work. Within days, and after interviews with several prominent firms, he was hired as a draftsman with the architectural firm of Joseph Lyman Silsbee.[8] Wright previously collaborated with Silsbee—accredited as the draftsman and the construction supervisor—on the 1886 Unity Chapel for Wright's family in Spring Green, Wisconsin.[9] While with the firm, he also worked on two other family projects: All Souls Church in Chicago for his uncle, Jenkin Lloyd Jones, and the Hillside Home School I in Spring Green for two of his aunts.[10] Other draftsmen who worked for Silsbee in 1887 included future architects Cecil Corwin, George W. Maher, and George G. Elmslie. Wright soon befriended Corwin, with whom he lived until he found a permanent home.

The Walter Gale House (1893) is Queen Anne in style yet features window bands and a cantilevered porch roof which hint at Wright's developing aesthetics

In his autobiography, Wright recounts that he also had a short stint in another Chicago architecture office. Feeling that he was underpaid for the quality of his work for Silsbee (at $8 a week), the young draftsman quit and found work as a designer at the firm of Beers, Clay, and Dutton. However, Wright soon realized that he was not ready to handle building design by himself; he left his new job to return to Joseph Silsbee—this time with a raise in salary.[11]

Although Silsbee adhered mainly to Victorian and revivalist architecture, Wright found his work to be more "gracefully picturesque" than the other "brutalities" of the period.[12] Still, Wright aspired for more progressive work. After less than a year had passed in Silsbee's office, Wright learned that the Chicago firm of Adler & Sullivan was "looking for someone to make the finish drawings for the interior of the Auditorium [Building]".[13] Wright demonstrated that he was a competent impressionist of Louis Sullivan's ornamental designs and two short interviews later, was an official apprentice in the firm.[14]

Wright did not get along well with Sullivan's other draftsmen; he wrote that several violent altercations occurred between them during the first years of his apprenticeship. For that matter, Sullivan showed very little respect for his employees as well.[15] In spite of this, "Sullivan took [Wright] under his wing and gave him great design responsibility." As an act of respect, Wright would later refer to Sullivan as Lieber Meister (German for "Dear Master").[16] He also formed a bond with office foreman Paul Mueller. Wright would later engage Mueller to build several of his public and commercial buildings between 1903 and 1923.[17]

On June 1, 1889, Wright married his first wife, Catherine Lee "Kitty" Tobin (1871–1959). The two had met around a year earlier during activities at All Souls Church. Sullivan did his part to facilitate the financial success of the young couple by granting Wright a five-year employment contract. Wright made one more request: "Mr. Sullivan, if you want me to work for you as long as five years, couldn't you lend me enough money to build a little house?"[18] With Sullivan's $5,000 loan, Wright purchased a lot at the corner of Chicago and Forest Avenues in the suburb of Oak Park. The existing Gothic Revival house was given to his mother, while a compact Shingle style house was built alongside for Wright and Catherine.[19]

According to an 1890 diagram of the firm's new, 17th floor space atop the Auditorium Building, Wright soon earned a private office next to Sullivan's own.[17] However, that office was actually shared with friend and draftsman George Elmslie, who was hired by Sullivan at Wright's request.[20] Wright had risen to head draftsman and handled all residential design work in the office. As a general rule, Adler & Sullivan did not design or build houses, but they obliged when asked by the clients of their important commercial projects. Wright was occupied by the firm's major commissions during office hours, so house designs were relegated to evening and weekend overtime hours at his home studio. He would later claim total responsibility for the design of these houses, but careful inspection of their architectural style and accounts from historian Robert Twombly suggest that it was Sullivan who dictated the overall form and motifs of the residential works; Wright's design duties were often reduced to detailing the projects from Sullivan's sketches.[20] During this time, Wright worked on Sullivan's bungalow (1890) and the James A. Charnley bungalow (1890) both in Ocean Springs, Mississippi, the Berry-MacHarg House (1891) and Louis Sullivan's House (1892) both in Chicago, and the most noted 1891 James A. Charnley House also in Chicago. Of the five collaborations, only the two commissions for the Charnley family still stand.[21][22]

Despite Sullivan's loan and overtime salary, Wright was constantly short on funds. Wright admitted that his poor finances were likely due to his expensive tastes in wardrobe and vehicles, and the extra luxuries he designed into his house. To supplement his income and repay his debts, Wright accepted independent commissions for at least nine houses. These "bootlegged" houses, as he later called them, were conservatively designed in variations of the fashionable Queen Anne and Colonial Revival styles. Nevertheless, unlike the prevailing architecture of the period, each house emphasized simple geometric massing and contained features such as bands of horizontal windows, occasional cantilevers, and open floor plans which would become hallmarks of his later work. Eight of these early houses remain today including the Thomas Gale, Robert P. Parker House, George Blossom, and Walter Gale houses.[23]

As with the residential projects for Adler & Sullivan, he designed his bootleg houses on his own time. Sullivan knew nothing of the independent works until 1893, when he recognized that one of the houses was unmistakably a Frank Lloyd Wright design. This particular house, built for Allison Harlan, was only blocks away from Sullivan's townhouse in the Chicago community of Kenwood. Aside from the location, the geometric purity of the composition and balcony tracery in the same style as the Charnley House likely gave away Wright's involvement. Since Wright's five-year contract forbade any outside work, the incident led to his departure from Sullivan's firm.[22] A variety of stories recount the break in the relationship between Sullivan and Wright; even Wright later told two different versions of the occurrence. In An Autobiography, Wright claimed that he was unaware that his side ventures were a breach of his contract. When Sullivan learned of them, he was angered and offended; he prohibited any further outside commissions and refused to issue Wright the deed to his Oak Park house until after he completed his five years. Wright could not bear the new hostility from his master and thought the situation was unjust. He "threw down [his] pencil and walked out of the Adler and Sullivan office never to return." Dankmar Adler, who was more sympathetic to Wright's actions, later sent him the deed.[24] On the other hand, Wright told his Taliesin apprentices (as recorded by Edgar Tafel) that Sullivan fired him on the spot upon learning of the Harlan House. Tafel also accounted that Wright had Cecil Corwin sign several of the bootleg jobs, indicating that Wright was aware of their illegal nature.[22][25] Regardless of the correct series of events, Wright and Sullivan did not meet or speak for twelve years.

His work includes original and innovative examples of many building types, including offices, churches, schools, skyscrapers, hotels, and museums. Wright also designed many of the interior elements of his buildings, such as the furniture and stained glass. Wright wrote 20 books and many articles and was a popular lecturer in the United States and in Europe. His colorful personal life often made headlines, most notably for the 1914 fire and murders at his Taliesin studio. Already well known during his lifetime, Wright was recognized in 1991 by the American Institute of Architects as "the greatest American architect of all time".[1]

Frank Lloyd Wright was born Frank Lincoln Wright in the farming town of Richland Center, Wisconsin, United States, in 1867. His father, William Carey Wright (1825–1904), was a locally admired orator, music teacher, occasional lawyer, and itinerant minister. William Wright met and married Anna Lloyd Jones (1838/39 – 1923), a county school teacher, the previous year when he was employed as the superintendent of schools for Richland County. Originally from Massachusetts, William Wright had been a Baptist minister, but he later joined his wife's family in the Unitarian faith. Anna was a member of the large, prosperous and well-known Lloyd Jones family of Unitarians, who had emigrated from Wales to Spring Green, Wisconsin. One of Anna's brothers was Jenkin Lloyd Jones, who would become an important figure in the spread of the Unitarian faith in the Western United States. Both of Wright's parents were strong-willed individuals with idiosyncratic interests that they passed on to him. According to his biography, his mother declared when she was expecting that her first child would grow up to build beautiful buildings. She decorated his nursery with engravings of English cathedrals torn from a periodical to encourage the infant's ambition.[2] The family moved to Weymouth, Massachusetts in 1870 for William to minister a small congregation.

Wright's home in Oak Park, Illinois

In 1876, Anna visited the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia and saw an exhibit of educational blocks created by Friedrich Wilhelm August Fröbel. The blocks, known as Froebel Gifts, were the foundation of his innovative kindergarten curriculum. A trained teacher, Anna was excited by the program and bought a set of blocks for her family. Young Wright spent much time playing with the blocks. These were geometrically shaped and could be assembled in various combinations to form three-dimensional compositions. This is how Wright described, in his autobiography, the influence of these exercises on his approach to design: "For several years I sat at the little Kindergarten table-top ... and played ... with the cube, the sphere and the triangle—these smooth wooden maple blocks ... All are in my fingers to this day ..."[3] Many of his buildings are notable for their geometrical clarity.

The Wright family struggled financially in Weymouth and returned to Spring Green, Wisconsin, where the supportive Lloyd Jones clan could help William find employment. They settled in Madison, where William taught music lessons and served as the secretary to the newly formed Unitarian society. Although William was a distant parent, he shared his love of music, especially the works of Johann Sebastian Bach, with his children.

Soon after Wright turned 14, his parents separated. Anna had been unhappy for some time with William's inability to provide for his family and asked him to leave. The divorce was finalized in 1885 after William sued Anna for lack of physical affection. William left Wisconsin after the divorce and Wright claimed he never saw his father again.[4] At this time he changed his middle name from Lincoln to Lloyd in honor of his mother's family, the Lloyd Joneses. As the only male left in the family, Wright assumed financial responsibility for his mother and two sisters.

Wright attended Madison High School, but there is no evidence he ever graduated.[5] He was admitted to the University of Wisconsin–Madison as a special student in 1886. There he joined Phi Delta Theta fraternity,[6] took classes part-time for two semesters, and worked with a professor of civil engineering, Allan D. Conover.[7] . In 1887, Wright left the school without taking a degree (although he was granted an honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts from the University in 1955) and arrived in Chicago in search of employment. As a result of the devastating Great Chicago Fire of 1871 and recent population boom, new development was plentiful in the city. He later recalled that his first impressions of Chicago were that of grimy neighborhoods, crowded streets, and disappointing architecture, yet he was determined to find work. Within days, and after interviews with several prominent firms, he was hired as a draftsman with the architectural firm of Joseph Lyman Silsbee.[8] Wright previously collaborated with Silsbee—accredited as the draftsman and the construction supervisor—on the 1886 Unity Chapel for Wright's family in Spring Green, Wisconsin.[9] While with the firm, he also worked on two other family projects: All Souls Church in Chicago for his uncle, Jenkin Lloyd Jones, and the Hillside Home School I in Spring Green for two of his aunts.[10] Other draftsmen who worked for Silsbee in 1887 included future architects Cecil Corwin, George W. Maher, and George G. Elmslie. Wright soon befriended Corwin, with whom he lived until he found a permanent home.

The Walter Gale House (1893) is Queen Anne in style yet features window bands and a cantilevered porch roof which hint at Wright's developing aesthetics

In his autobiography, Wright recounts that he also had a short stint in another Chicago architecture office. Feeling that he was underpaid for the quality of his work for Silsbee (at $8 a week), the young draftsman quit and found work as a designer at the firm of Beers, Clay, and Dutton. However, Wright soon realized that he was not ready to handle building design by himself; he left his new job to return to Joseph Silsbee—this time with a raise in salary.[11]

Although Silsbee adhered mainly to Victorian and revivalist architecture, Wright found his work to be more "gracefully picturesque" than the other "brutalities" of the period.[12] Still, Wright aspired for more progressive work. After less than a year had passed in Silsbee's office, Wright learned that the Chicago firm of Adler & Sullivan was "looking for someone to make the finish drawings for the interior of the Auditorium [Building]".[13] Wright demonstrated that he was a competent impressionist of Louis Sullivan's ornamental designs and two short interviews later, was an official apprentice in the firm.[14]

Wright did not get along well with Sullivan's other draftsmen; he wrote that several violent altercations occurred between them during the first years of his apprenticeship. For that matter, Sullivan showed very little respect for his employees as well.[15] In spite of this, "Sullivan took [Wright] under his wing and gave him great design responsibility." As an act of respect, Wright would later refer to Sullivan as Lieber Meister (German for "Dear Master").[16] He also formed a bond with office foreman Paul Mueller. Wright would later engage Mueller to build several of his public and commercial buildings between 1903 and 1923.[17]

On June 1, 1889, Wright married his first wife, Catherine Lee "Kitty" Tobin (1871–1959). The two had met around a year earlier during activities at All Souls Church. Sullivan did his part to facilitate the financial success of the young couple by granting Wright a five-year employment contract. Wright made one more request: "Mr. Sullivan, if you want me to work for you as long as five years, couldn't you lend me enough money to build a little house?"[18] With Sullivan's $5,000 loan, Wright purchased a lot at the corner of Chicago and Forest Avenues in the suburb of Oak Park. The existing Gothic Revival house was given to his mother, while a compact Shingle style house was built alongside for Wright and Catherine.[19]

According to an 1890 diagram of the firm's new, 17th floor space atop the Auditorium Building, Wright soon earned a private office next to Sullivan's own.[17] However, that office was actually shared with friend and draftsman George Elmslie, who was hired by Sullivan at Wright's request.[20] Wright had risen to head draftsman and handled all residential design work in the office. As a general rule, Adler & Sullivan did not design or build houses, but they obliged when asked by the clients of their important commercial projects. Wright was occupied by the firm's major commissions during office hours, so house designs were relegated to evening and weekend overtime hours at his home studio. He would later claim total responsibility for the design of these houses, but careful inspection of their architectural style and accounts from historian Robert Twombly suggest that it was Sullivan who dictated the overall form and motifs of the residential works; Wright's design duties were often reduced to detailing the projects from Sullivan's sketches.[20] During this time, Wright worked on Sullivan's bungalow (1890) and the James A. Charnley bungalow (1890) both in Ocean Springs, Mississippi, the Berry-MacHarg House (1891) and Louis Sullivan's House (1892) both in Chicago, and the most noted 1891 James A. Charnley House also in Chicago. Of the five collaborations, only the two commissions for the Charnley family still stand.[21][22]

Despite Sullivan's loan and overtime salary, Wright was constantly short on funds. Wright admitted that his poor finances were likely due to his expensive tastes in wardrobe and vehicles, and the extra luxuries he designed into his house. To supplement his income and repay his debts, Wright accepted independent commissions for at least nine houses. These "bootlegged" houses, as he later called them, were conservatively designed in variations of the fashionable Queen Anne and Colonial Revival styles. Nevertheless, unlike the prevailing architecture of the period, each house emphasized simple geometric massing and contained features such as bands of horizontal windows, occasional cantilevers, and open floor plans which would become hallmarks of his later work. Eight of these early houses remain today including the Thomas Gale, Robert P. Parker House, George Blossom, and Walter Gale houses.[23]

As with the residential projects for Adler & Sullivan, he designed his bootleg houses on his own time. Sullivan knew nothing of the independent works until 1893, when he recognized that one of the houses was unmistakably a Frank Lloyd Wright design. This particular house, built for Allison Harlan, was only blocks away from Sullivan's townhouse in the Chicago community of Kenwood. Aside from the location, the geometric purity of the composition and balcony tracery in the same style as the Charnley House likely gave away Wright's involvement. Since Wright's five-year contract forbade any outside work, the incident led to his departure from Sullivan's firm.[22] A variety of stories recount the break in the relationship between Sullivan and Wright; even Wright later told two different versions of the occurrence. In An Autobiography, Wright claimed that he was unaware that his side ventures were a breach of his contract. When Sullivan learned of them, he was angered and offended; he prohibited any further outside commissions and refused to issue Wright the deed to his Oak Park house until after he completed his five years. Wright could not bear the new hostility from his master and thought the situation was unjust. He "threw down [his] pencil and walked out of the Adler and Sullivan office never to return." Dankmar Adler, who was more sympathetic to Wright's actions, later sent him the deed.[24] On the other hand, Wright told his Taliesin apprentices (as recorded by Edgar Tafel) that Sullivan fired him on the spot upon learning of the Harlan House. Tafel also accounted that Wright had Cecil Corwin sign several of the bootleg jobs, indicating that Wright was aware of their illegal nature.[22][25] Regardless of the correct series of events, Wright and Sullivan did not meet or speak for twelve years.

_________________

We don't care the People Says , Rock 'n' roll is here to stay - Danny & the Juniors - 1958

Re: Frank Lloyd Wright - 1867 / 1959

Re: Frank Lloyd Wright - 1867 / 1959

After leaving Louis Sullivan, Wright established his own practice on the top floor of the Sullivan designed Schiller Building (1892, demolished 1961) on Randolph Street in Chicago. Wright chose to locate his office in the building because the tower location reminded him of the office of Adler & Sullivan. Although Cecil Corwin followed Wright and set up his architecture practice in the same office, the two worked independently and did not consider themselves partners.[26] Within a year, Corwin decided that he did not enjoy architecture and journeyed east to find a new profession.[27]

With Corwin gone, Wright moved out of the Schiller Building and into the nearby and newly completed Steinway Hall Building. The loft space was shared with Robert C. Spencer, Jr., Myron Hunt, and Dwight H. Perkins.[28] These young architects, inspired by the Arts and Crafts Movement and the philosophies of Louis Sullivan, formed what would become known as the Prairie School.[29] They were joined by Perkins apprentice, Marion Mahony, who in 1895 transferred to Wright's team of drafters and took over production of his presentation drawings and watercolor renderings. Mahony, the third woman to be licensed as an architect in Illinois and one of the first licensed female architects in the U.S., also designed furniture, leaded glass windows, and light fixtures, among other features, for Wright's houses.[30][31] Between 1894 and the early 1910s, several other leading Prairie School architects and many of Wright's future employees launched their careers in the offices of Steinway Hall.

William H. Winslow House (1893) in River Forest, Illinois

Wright's projects during this period followed two basic models. On one hand, there was his first independent commission, the Winslow House, which combined Sullivanesque ornamentation with the emphasis on simple geometry and horizontal lines that is typical in Wright houses. The Francis Apartments (1895, demolished 1971), Heller House (1896), Rollin Furbeck House (1897), and Husser House (1899, demolished 1926) were designed in the same mode. For more conservative clients, Wright conceded to design more traditional dwellings. These included the Dutch Colonial Revival style Bagley House (1894), Tudor Revival style Moore House I (1895), and Queen Anne style Charles E. Roberts House (1896).[32] As an emerging architect, Wright could not afford to turn down clients over disagreements in taste, but even his most conservative designs retained simplified massing and occasional Sullivan inspired details.[33]

Soon after the completion of the Winslow House in 1894, Edward Waller, a friend and former client, invited Wright to meet Chicago architect and planner Daniel Burnham. Burnham had been impressed by the Winslow House and other examples of Wright's work; he offered to finance a four-year education at the École des Beaux-Arts and two years in Rome. To top it off, Wright would have a position in Burnham's firm upon his return. In spite of guaranteed success and support of his family, Wright declined the offer. Burnham, who had directed the classical design of the World's Columbian Exposition was a major proponent of the Beaux Arts movement, thought that Wright was making a foolish mistake. Yet for Wright, the classical education of the École lacked creativity and was altogether at odds with his vision of modern American architecture.[34][35]

Wright relocated his practice to his home in 1898 in order to bring his work and family lives closer. This move made further sense as the majority of the architect's projects at that time were in Oak Park or neighboring River Forest. The past five years had seen the birth of three more children — Catherine in 1894, David in 1895, and Frances in 1898 — prompting Wright to sacrifice his original home studio space for additional bedrooms. Thus, moving his workspace necessitated his design and construction of an expansive studio addition to the north of the main house. The space, which included a hanging balcony within the two story drafting room, was one of Wright's first experiments with innovative structure. The studio was a poster for Wright's developing aesthetics and would become the laboratory from which the next ten years of architectural creations would emerge.[36] The renovation included a playroom with high vaulted ceilings for his children. The fireplace takes up the majority of one wall of the playroom. A skylight at the top of the arc runs almost the length of the room. Made of Roman brick, the fireplace lies below a mural from the story "The Fisherman and the Genie" from Arabian Nights created by the artist Charles Corwin. Wright believed that the fireplace was an integral architectural feature within the home, often calling the hearth the heart of the home.[37][38]

With Corwin gone, Wright moved out of the Schiller Building and into the nearby and newly completed Steinway Hall Building. The loft space was shared with Robert C. Spencer, Jr., Myron Hunt, and Dwight H. Perkins.[28] These young architects, inspired by the Arts and Crafts Movement and the philosophies of Louis Sullivan, formed what would become known as the Prairie School.[29] They were joined by Perkins apprentice, Marion Mahony, who in 1895 transferred to Wright's team of drafters and took over production of his presentation drawings and watercolor renderings. Mahony, the third woman to be licensed as an architect in Illinois and one of the first licensed female architects in the U.S., also designed furniture, leaded glass windows, and light fixtures, among other features, for Wright's houses.[30][31] Between 1894 and the early 1910s, several other leading Prairie School architects and many of Wright's future employees launched their careers in the offices of Steinway Hall.

William H. Winslow House (1893) in River Forest, Illinois

Wright's projects during this period followed two basic models. On one hand, there was his first independent commission, the Winslow House, which combined Sullivanesque ornamentation with the emphasis on simple geometry and horizontal lines that is typical in Wright houses. The Francis Apartments (1895, demolished 1971), Heller House (1896), Rollin Furbeck House (1897), and Husser House (1899, demolished 1926) were designed in the same mode. For more conservative clients, Wright conceded to design more traditional dwellings. These included the Dutch Colonial Revival style Bagley House (1894), Tudor Revival style Moore House I (1895), and Queen Anne style Charles E. Roberts House (1896).[32] As an emerging architect, Wright could not afford to turn down clients over disagreements in taste, but even his most conservative designs retained simplified massing and occasional Sullivan inspired details.[33]

Soon after the completion of the Winslow House in 1894, Edward Waller, a friend and former client, invited Wright to meet Chicago architect and planner Daniel Burnham. Burnham had been impressed by the Winslow House and other examples of Wright's work; he offered to finance a four-year education at the École des Beaux-Arts and two years in Rome. To top it off, Wright would have a position in Burnham's firm upon his return. In spite of guaranteed success and support of his family, Wright declined the offer. Burnham, who had directed the classical design of the World's Columbian Exposition was a major proponent of the Beaux Arts movement, thought that Wright was making a foolish mistake. Yet for Wright, the classical education of the École lacked creativity and was altogether at odds with his vision of modern American architecture.[34][35]